Type a search term to find related articles by LIMS subject matter experts gathered from the most trusted and dynamic collaboration tools in the laboratory informatics industry.

| Berber | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tamazight Amazigh تَمَزِيغت Tamaziɣt ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵣⵉⵖⵜ | |||

| Geographic distribution | Scattered communities across parts of North Africa and Berber diaspora | ||

| Ethnicity | Berbers | ||

| Linguistic classification | Afro-Asiatic

| ||

| Proto-language | Proto-Berber | ||

| Subdivisions | |||

| Language codes | |||

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | ber | ||

| Glottolog | berb1260 | ||

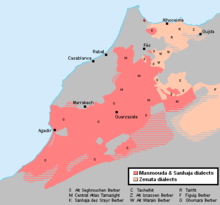

Berber-speaking populations are dominant in the coloured areas of Africa. Other areas, especially in North Africa, contain minority Berber-speaking populations.

| |||

The Berber languages, also known as the Amazigh languages[a] or Tamazight,[b] are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family.[1][2] They comprise a group of closely related but mostly mutually unintelligible languages[3] spoken by Berber communities, who are indigenous to North Africa.[4][5] The languages are primarily spoken and not typically written.[6] Historically, they have been written with the ancient Libyco-Berber script, which now exists in the form of Tifinagh.[7][8] Today, they may also be written in the Berber Latin alphabet or the Arabic script, with Latin being the most pervasive.[9][10][11]

The Berber languages have a similar level of variety to the Romance languages, although they are sometimes referred to as a single collective language, often as "Berber", "Tamazight", or "Amazigh".[12][13][14][15] The languages, with a few exceptions, form a dialect continuum.[12] There is a debate as to how to best sub-categorize languages within the Berber branch.[12][16] Berber languages typically follow verb–subject–object word order.[17][18] Their phonological inventories are diverse.[16]

Millions of people in Morocco and Algeria natively speak a Berber language, as do smaller populations of Libya, Tunisia, northern Mali, western and northern Niger, northern Burkina Faso and Mauritania and the Siwa Oasis of Egypt.[19] There are also probably a few million speakers of Berber languages in Western Europe.[20] Tashlhiyt, Kabyle, Central Atlas Tamazight, Tarifit, and Shawiya are some of the most commonly spoken Berber languages.[19] Exact numbers are impossible to ascertain as there are few modern North African censuses that include questions on language use, and what censuses do exist have known flaws.[21]

Following independence in the 20th century, the Berber languages have been suppressed and suffered from low prestige in North Africa.[21] Recognition of the Berber languages has been growing in the 21st century, with Morocco and Algeria adding Tamazight as an official language to their constitutions in 2011 and 2016 respectively.[21][22][23]

Most Berber languages have a high percentage of borrowing and influence from the Arabic language, as well as from other languages.[24] For example, Arabic loanwords represent 35%[25] to 46%[26] of the total vocabulary of the Kabyle language and represent 51.7% of the total vocabulary of Tarifit.[27] Almost all Berber languages took from Arabic the pharyngeal fricatives /ʕ/ and /ħ/, the (nongeminated) uvular stop /q/, and the voiceless pharyngealized consonant /ṣ/.[28] Unlike the Chadic, Cushitic, and Omotic languages of the Afro-Asiatic phylum, Berber languages are not tonal languages.[29][30]

"Tamazight" and "Berber languages" are often used interchangeably.[13][14][31] However, "Tamazight" is sometimes used to refer to a specific subset of Berber languages, such as Central Tashlhiyt.[32] "Tamazight" can also be used to refer to Standard Moroccan Tamazight or Standard Algerian Tamazight, as in the Moroccan and Algerian constitutions respectively.[33][34] In Morocco, besides referring to all Berber languages or to Standard Moroccan Tamazight, "Tamazight" is often used in contrast to Tashelhit and Tarifit to refer to Central Atlas Tamazight.[35][36][37][38]

The use of Berber has been the subject of debate due to its historical background as an exonym and present equivalence with the Arabic word for "barbarian."[39][40][41][42] One group, the Linguasphere Observatory, has attempted to introduce the neologism "Tamazic languages" to refer to the Berber languages.[43] Amazigh people typically use "Tamazight" when speaking English.[44] Historically, Berbers did not refer to themselves as Berbers/Amazigh but had their own terms to refer to themselves. For example, the Kabyles use the term "Leqbayel" to refer to their own people, while the Chaouis identified themselves as "Ishawiyen" instead of Berber/Amazigh.[45]

Since modern Berber languages are relatively homogeneous, the date of the Proto-Berber language from which the modern group is derived was probably comparatively recent, comparable to the age of the Germanic or Romance subfamilies of the Indo-European family. In contrast, the split of the group from the other Afroasiatic sub-phyla is much earlier, and is therefore sometimes associated with the local Mesolithic Capsian culture.[46] A number of extinct populations are believed to have spoken Afroasiatic languages of the Berber branch. According to Peter Behrens and Marianne Bechaus-Gerst, linguistic evidence suggests that the peoples of the C-Group culture in present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan spoke Berber languages.[47][48] The Nilo-Saharan Nobiin language today contains a number of key loanwords related to pastoralism that are of Berber origin, including the terms for sheep and water/Nile. This in turn suggests that the C-Group population—which, along with the Kerma culture, inhabited the Nile valley immediately before the arrival of the first Nubian speakers—spoke Afroasiatic languages.[47]

Berber languages are primarily oral languages without a major written component.[6] Historically, they were written with the Libyco-Berber script. Early uses of the script have been found on rock art and in various sepulchres; the oldest known variations of the script dates to inscriptions in Dugga from 600 BC.[6][49][50] Usage of this script, in the form of Tifinagh, has continued into the present day among the Tuareg people.[51] Following the spread of Islam, some Berber scholars also utilized the Arabic script.[52] The Berber Latin alphabet was developed following the introduction of the Latin script in the nineteenth century by the West.[51] The nineteenth century also saw the development of Neo-Tifinagh, an adaptation of Tuareg Tifinagh for use with other Berber languages.[6][53][54]

There are now three writing systems in use for Berber languages: Tifinagh, the Arabic script, and the Berber Latin alphabet, with the Latin alphabet being the most widely used today.[10][11]

With the exception of Zenaga, Tetserret, and Tuareg, the Berber languages form a dialect continuum. Different linguists take different approaches towards drawing boundaries between languages in this continuum.[12] Maarten Kossmann notes that it is difficult to apply the classic tree model of historical linguistics towards the Berber languages:

[The Berber language family]'s continuous history of convergence and differentiation along new lines makes an definition of branches arbitrary. Moreover, mutual intelligibility and mutual influence render notions such as "split" or "branching" rather difficult to apply except, maybe, in the case of Zenaga and Tuareg.[55]

Kossmann roughly groups the Berber languages into seven blocks:[55]

The Zenatic block is typically divided into the Zenati and Eastern Berber branches, due to the marked difference in features at each end of the continuum.[56][55][57] Otherwise, subclassifications by different linguists typically combine various blocks into different branches. Western Moroccan languages, Zenati languages, Kabyle, and Ghadames may be grouped under Northern Berber; Awjila is often included as an Eastern Berber language alongside Siwa, Sokna, and El Foqaha. These approaches divide the Berber languages into Northern, Southern (Tuareg), Eastern, and Western varieties.[56][57]

The vast majority of speakers of Berber languages are concentrated in Morocco and Algeria.[58][59] The exact population of speakers has been historically difficult to ascertain due to lack of official recognition.[60]

Morocco is the country with the greatest number of speakers of Berber languages.[58][59][61] As of 2022, Ethnologue estimates there to be 13.8 million speakers of Berber languages in Morocco, based on figures from 2016 and 2017.[62]

In 1960, the first census after Moroccan independence was held. It claimed that 32 percent of Moroccans spoke a Berber language, including bi-, tri- and quadrilingual people.[63] The 2004 census found that 3,894,805 Moroccans over five years of age spoke Tashelhit, 2,343,937 spoke Central Atlas Tamazight, and 1,270,986 spoke Tarifit, representing 14.6%, 8.8%, and 4.8% respectively of the surveyed population, or roughly 28.2% of the surveyed population combined.[64] The 2014 census found that 14.1% of the population spoke Tashelhit, 7.9% spoke Central Atlas Tamazight, and 4% spoke Tarifit, or about 26% of the population combined.[65]

These estimates, as well as the estimates from various academic sources, are summarized as follows:

| Source | Date | Total | Tashelhit | Central Atlas Tamazight | Tarifit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamazight of the Ayt Ndhir[59] | 1973 | 6 million | – | – | – | Extrapolating from Basset's 1952 La langue berbère based on overall population changes. |

| Ethnologue[44][58] | 2001 | 7.5 million | 3 million | 3 million | 1.5 million | -- |

| Moroccan census[64] | 2004 | 7.5 million | 3.9 million | 2.3 million | 1.3 million | Also used by Ethnologue in 2015.[66] Only individuals over age 5 were included. |

| Multilingualism, Cultural Identity, and Education in Morocco[61] | 2005 | 15 million | 6.8 million | 5.2 million | 3 million | Also used in Semitic and Afroasiatic: Challenges and Opportunities in 2012.[67] |

| Moroccan census[68] | 2014 | 8.7 million | 4.7 million | 2.7 million | 1.3 million | Calculated via reported percentages. As in the 2004 census, only individuals over age 5 were surveyed for language. |

| Ethnologue[62] | 2022 | 13.8 million | 5 million | 4.6 million | 4.2 million | Additional Berber languages include Senhaja Berber (86,000 speakers) and Ghomara (10,000 speakers). |

Algeria is the country with the second greatest number of speakers of Berber languages.[58][59] In 1906, the total population speaking Berber languages in Algeria, excluding the thinly populated Sahara region, was estimated at 1,305,730 out of 4,447,149, or 29%.[69] Secondary sources disagree on the percentage of self-declared native Berber speakers in the 1966 census, the last Algerian census containing a question about the mother tongue. Some give 17.9%[70][71][72][73] while other report 19%.[74][75]

Kabyle speakers account for the vast majority of speakers of Berber languages in Algeria. Shawiya is the second most commonly spoken Berber language in Algeria. Other Berber languages spoken in Algeria include: Shenwa, with 76,300 speakers; Tashelhit, with 6,000 speakers; Ouargli, with 20,000 speakers; Tamahaq, with 71,400 speakers; Tugurt, with 8,100 speakers; Tidikelt, with 1,000 speakers; Gurara, with 11,000 speakers; and Mozabite, with 150,000 speakers.[76][77]

Population estimates are summarized as follows:

| Source | Date | Total | Kabyle | Shawiya | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annales de Géographie[69] | 1906 | 1.3 million | – | – | – |

| Textes en linguistique berbère[78] | 1980 | 3.6 million | -- | -- | -- |

| International Encyclopedia of Linguistics[79] | 2003 | -- | 2.5 million | -- | -- |

| Language Diversity Endangered[80] | 2015 | 4.5 million | 2.5 million - 3 million | 1.4 million | 0.13 million - 0.190 million |

| Journal of African Languages and Literatures[81] | 2021 | -- | 3 million | -- | -- |

As of 1998, there were an estimated 450,000 Tawellemmet speakers, 250,000 Air Tamajeq speakers, and 20,000 Tamahaq speakers in Niger.[82]

As of 2018 and 2014 respectively, there were an estimated 420,000 speakers of Tawellemmet and 378,000 of Tamasheq in Mali.[82][83]

As of 2022, based on figures from 2020, Ethnologue estimates there to be 285,890 speakers of Berber languages in Libya: 247,000 speakers of Nafusi, 22,800 speakers of Tamahaq, 13,400 speakers of Ghadamés, and 2,690 speakers of Awjila. The number of Siwi speakers in Libya is listed as negligible, and the last Sokna speaker is thought to have died in the 1950s.[84]

There are an estimated 50,000 Djerbi speakers in Tunisia, based on figures from 2004. Sened is likely extinct, with the last speaker having died in the 1970s. Ghadamés, though not indigenous to Tunisia, is estimated to have 3,100 speakers throughout the country.[85] Chenini is one of the rare remaining Berber-speaking villages in Tunisia.[86]

There are an estimated 20,000 Siwi speakers in Egypt, based on figures from 2013.[87]

As of 2018 and 2017 respectively, there were an estimated 200 speakers of Zenaga and 117,000 of Tamasheq in Mauritania.[88]

As of 2009, there were an estimated 122,000 Tamasheq speakers in Burkina Faso.[89]

There are an estimated 1.5 million speakers of various Berber languages in France.[90] A small number of Tawellemmet speakers live in Nigeria.[91]

In total, there are an estimated 3.6 million speakers of Berber languages in countries outside of Morocco and Algeria, summarized as follows:

| Total | Niger | Mali | Libya | Tunisia | Egypt | Mauritania | Burkina Faso | France |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,577,300 | 720,000[82] | 798,000[83] | 247,000[84] | 53,100[85] | 20,000[87] | 117,200[88] | 122,000[89] | 1,500,000[90] |

After independence, all the Maghreb countries to varying degrees pursued a policy of Arabisation, aimed partly at displacing French from its colonial position as the dominant language of education and literacy. Under this policy the use of the Berber languages was suppressed or even banned. This state of affairs has been contested by Berbers in Morocco and Algeria—especially Kabylie—and was addressed in both countries by affording the language official status and introducing it in some schools.

After gaining independence from France in 1956, Morocco began a period of Arabisation through 1981, with primary and secondary school education gradually being changed to Arabic instruction, and with the aim of having administration done in Arabic, rather than French. During this time, there were riots amongst the Amazigh population, which called for the inclusion of Tamazight as an official language.[92]

The 2000 Charter for Education Reform marked a change in policy, with its statement of "openness to Tamazight."[93]

Planning for a public Tamazight-language TV network began in 2006; in 2010, the Moroccan government launched Tamazight TV.[40]

On July 29, 2011, Tamazight was added as an official language to the Moroccan constitution.[22]

After gaining independence from France in 1962, Algeria committed to a policy of Arabisation, which, after the imposition of the Circular of July 1976, encompassed the spheres of education, public administration, public signage, print publication, and the judiciary. While primarily directed towards the erasure of French in Algerian society, these policies also targeted Berber languages, leading to dissatisfaction and unrest amongst speakers of Berber languages, who made up about one quarter of the population.[94]

After the 1994-1995 general school boycott in Kabylia, Tamazight was recognized for the first time as a national language.[95] In 2002, following the riots of the Black Spring, Tamazight was recognized for the second time as a national language, though not as an official one.[96][97] This was done on April 8, 2003.[94]

Tamazight has been taught for three hours a week through the first three years of Algerian middle schools since 2005.[94]

On January 5, 2016, it was announced that Tamazight had been added as a national and official language in a draft amendment to the Algerian constitution; it was added to the constitution as a national and official language on February 7, 2016.[98][99][33][23]

Although regional councils in Libya's Nafusa Mountains affiliated with the National Transitional Council reportedly use the Berber language of Nafusi and have called for it to be granted co-official status with Arabic in a prospective new constitution,[100][101] it does not have official status in Libya as in Morocco and Algeria. As areas of Libya south and west of Tripoli such as the Nafusa Mountains were taken from the control of Gaddafi government forces in early summer 2011, Berber workshops and exhibitions sprang up to share and spread the Berber culture and language.[102]

In Mali and Niger, some Tuareg languages have been recognized as national languages and have been part of school curriculums since the 1960s.[67]

In linguistics, the phonology of Berber languages is written with the International Phonetic Alphabet, with the following exceptions:[103]

| Notation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| /š/ | unvoiced anterior post-alveolar, as in Slavic languages and Lithuanian |

| /ž/ | voiced anterior post-alveolar, also in Slavic languages and Lithuanian |

| /ɣ/ | voiced uvular fricative (in IPA, this represents the voiced velar fricative) |

| /◌͑/ | voiced pharyngeal fricative |

| /h/ | laryngeal voiced consonant |

| /◌͗/ | glottal stop |

| /ř/ | strident flap or /r̝/, as in Czech |

| ! | indicates the following segment is emphatic |

The influence of Arabic, the process of spirantization, and the absence of labialization have caused the consonant systems of Berber languages to differ significantly by region.[16] Berber languages found north of, and in the northern half of, the Sahara have greater influence from Arabic, including that of loaned phonemes, than those in more southern regions, like Tuareg.[16][104] Most Berber languages in northern regions have additionally undergone spirantization, in which historical short stops have changed into fricatives.[105] Northern Berber languages (which is a subset of but not identical to Berber languages in geographically northern regions) commonly have labialized velars and uvulars, unlike other Berber languages.[104][106]

Two languages that illustrate the resulting range in consonant inventory across Berber languages are Ahaggar Tuareg and Kabyle; Kabyle has two more places of articulation and three more manners of articulation than Ahaggar Tuareg.[16]

There is still, however, common consonant features observed across Berber languages. Almost all Berber languages have bilabial, dental, palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal, and laryngeal consonants, and almost all consonants have a long counterpart.[107][108] All Berber languages, as is common in Afroasiatic languages, have pharyngealized consonants and phonemic gemination.[16][109][110] The consonants which may undergo gemination, and the positions in a word where gemination may occur, differ by language.[111] They have also been observed to have tense and lax consonants, although the status of tense consonants has been the subject of "considerable discussion" by linguists.[108]

The vowel systems of Berber languages also vary widely, with inventories ranging from three phonemic vowels in most Northern Berber languages, to seven in some Eastern Berber and Tuareg languages.[112] For example, Taselhiyt has the vowels /i/, /a/, and /u/, while Ayer Tuareg has the vowels /i/, /ə/, /u/, /e/, /ɐ/, /o/, and /a/.[112][113] Contrastive vowel length is rare in Berber languages. Tuareg languages had previously been reported to have contrastive vowel length, but this is no longer the leading analysis.[112] A complex feature of Berber vowel systems is the role of central vowels, which vary in occurrence and function across languages; there is a debate as to whether schwa is a proper phoneme of Northern Berber languages.[114]

Most Berber languages:

Phonetic correspondences between Berber languages are fairly regular.[118] Some examples, of varying importance and regularity, include [g/ž/y]; [k/š]; [l/ř/r]; [l/ž, ll/ddž]; [trill/ vocalized r]; [šš/ttš]; [ss/ttš]; [w/g/b]; [q/ɣ]; [h/Ø]; and [s-š-ž/h].[103] Words in various Berber languages are shown to demonstrate these phonetic correspondences as follows:[119]

| Tahaggart (Touareg) |

Tashlhiyt (Morocco) |

Kabyle (Algeria) |

Figuig (Morocco) |

Central Atlas Tamazight (Morocco) |

Tarifit (Morocco) |

Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| !oska | !uskay | !uššay | (Arabic loan) | !usça | !uššay | "greyhound" |

| t-a-!gzəl-t | t-i-!gzzl-t | t-i-!gzzəl-t | t-i-!yžəl-t | t-i-!ḡzəl-t | θ-i-!yzzətš | "kidney" |

| a-gelhim | a-glzim | a-gəlzim | a-yəlzim | a-ḡzzim | a-řizim | "axe" |

| éhéder | i-gidr | i-gider | (Arabic loan) | yidər | žiða: | "eagle" |

| t-adhan-t | t-adgal-t | t-addžal-t | t-ahžžal-t | t-adžal-t | θ-ažžat | "window" |

| élem | ilm | a-gwlim | ilem | iləm | iřem | "skin" |

| a-!hiyod | a-!žddid | a-!žəddžid | – | a-!ḡddžid | a-!žžið | "scabies" |

| a-gûhil | i-gigil | a-gužil | a-yužil | a-wižil | a-yužiř | "orphan" |

| t-immé | i-gnzi | t-a-gwənza | t-a-nyər-t | t-i-nir-t | θ-a-nya:-θ | "forehead" |

| t-ahor-t | t-aggur-t | t-abbur-t | (Arabic loan) | t-aggur-t | θ-!awwa:-θ | "door" |

| t-a-flu-t | t-i-flu-t | t-i-flu-t | – | t-iflu-t | -- | |

| a-fus | a-fus | a-fus | a-fus | (a-)fus | fus | "hand" |

Berber languages characteristically make frequent use of apophony in the form of ablaut.[120] Berber apophony has been historically analyzed as functioning similarly to the Semitic root, but this analysis has fallen out of favor due to the lexical significance of vowels in Berber languages, as opposed to their primarily grammatical significance in Semitic languages.[120]

The lexical categories of all Berber languages are nouns, verbs, pronouns, adverbs, and prepositions. With the exception of a handful of Arabic loanwords in most languages, Berber languages do not have proper adjectives. In Northern and Eastern Berber languages, adjectives are a subcategory of nouns; in Tuareg, relative clauses and stative verb forms are used to modify nouns instead.[121]

The gender, number, and case of nouns, as well as the gender, number, and person of verbs, are typically distinguished through affixes.[122][123] Arguments are described with word order and clitics.[124][17] When sentences have a verb, they essentially follow verb–subject–object word order, although some linguists believe alternate descriptors would better categorize certain languages, such as Taqbaylit.[17][18]

Berber languages have both independent and dependent pronouns, both of which distinguish between person and number. Gender is also typically distinguished in the second and third person, and sometimes in first person plural.[124]

Linguist Maarten Kossmann divides pronouns in Berber languages into three morphological groups:[124]

When clitics precede or follow a verb, they are almost always ordered with the indirect object first, direct object second, and andative-venitive deictic clitic last. An example in Tarifit is shown as follows:[124]

y-əwš

3SG:M-give:PAST

=as

=3SG:IO

=θ

=3SG:M:DO

=ið

=VEN

"He gave it to him (in this direction)." (Tarifit)

The allowed positioning of different kinds of clitics varies by language.[124]

Nouns are distinguished by gender, number, and case in most Berber languages, with gender being feminine or masculine, number being singular or plural, and case being in the construct or free state.[120][56][122] Some Arabic borrowings in Northern and Eastern Berber languages do not accept these affixes; they instead retain the Arabic article regardless of case, and follow Arabic patterns to express number and gender.[125][126]

Gender can be feminine or masculine, and can be lexically determined, or can be used to distinguish qualities of the noun.[120] For humans and "higher" animals (such as mammals and large birds), gender distinguishes sex, whereas for objects and "lesser" animals (such as insects and lizards), it distinguishes size. For some nouns, often fruits and vegetables, gender can also distinguish the specificity of the noun.[120][127] The ways in which gender is used to distinguish nouns is shown in as follows, with examples from Figuig:[120][127]

| Noun type | Feminine | Masculine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | Figuig example | Example gloss | Feature | Figuig example | Example gloss | |

| humans; higher animals | female | ta-sli-t | "bride" | male | a-sli | "groom" |

| objects; lesser animals | small | ta-ɣənžay-t | "spoon" | large | a-ɣənža | "large spoon" |

| varies, but typically fruits and vegetables | unit noun | ta-mlul-t | "(one) melon" | collective noun | a-mlul | "melons (in general)" |

| ti-mlal (plural) | "(specific) melons" | |||||

An example of nouns with lexically determined gender are the feminine t-lussi ("butter") and masculine a-ɣi ("buttermilk") in Figuig.[120] Mass nouns have lexically determined gender across Berber languages.[127]

Most Berber languages have two cases, which distinguish the construct state from the free state.[56][128] The construct state is also called the "construct case, "relative case," "annexed state" (état d'annexion), or the "nominative case"; the free state (état libre) is also called the "direct case" or "accusative case."[56] When present, case is always expressed through nominal prefixes and initial-vowel reduction.[56][128] The use of the marked nominative system and constructions similar to Split-S alignment varies by language.[18][56] Eastern Berber languages do not have case.[56][128]

Number can be singular or plural, which is marked with prefixation, suffixation, and sometimes apophony. Nouns usually are made plural by one of either suffixation or apophony, with prefixation applied independently. Specifics vary by language, but prefixation typically changes singular a- and ta- to plural i- and ti- respectively.[122] The number of mass nouns are lexically determined. For example, in multiple Berber languages, such as Figuig, a-ɣi ("buttermilk") is singular while am-an ("water") is plural.[127]

Nouns or pronouns — optionally extended with genitival pronominal affixes, demonstrative clitics, or pre-nominal elements, and then further modified by numerals, adjectives, possessive phrases, or relative clauses — can be built into noun phrases.[129] Possessive phrases in noun phrases must have a genitive proposition.[121][129]

There are a limited number of pre-nominal elements, which function similarly to pronoun syntactic heads of the noun phrase, and which can be categorized into three types as follows:[129]

Verb bases are formed by stems that are optionally extended by prefixes, with mood, aspect, and negation applied with a vocalic scheme. This form can then be conjugated with affixes to agree with person, number, and gender, which produces a word.[123][125]

Different linguists analyze and label aspects in the Berber languages very differently. Kossman roughly summarizes the basic stems which denote aspect as follows:[130]

Different languages may have more stems and aspects, or may distinguish within the above categories. Stem formation can be very complex, with Tuareg by some measures having over two hundred identified conjugation subtypes.[130]

The aspectual stems of some classes of verbs in various Berber languages are shown as follows:[131]

| Figuig | Ghadames | Ayer Tuareg | Mali Tuareg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aorist | əlmədatəf | ălmədatəf | əlmədatəf | əlmədaləm |

| Imperfective | ləmmədttatəf | lămmădttatăf | -- | lămmădtiləm |

| Secondary Imperfective | -- | -- | lámmădtátăf | lámmădtiləm |

| Negative Imperfective | ləmmədttitəf | ləmmədttitəf | ləmmədtitəf | ləmmədtiləm |

| Perfective | əlmədutəf | əlmădutăf | əlmădotăf | əlmădolăm |

| Secondary Perfective | -- | -- | əlmádotáf | əlmádolám |

| Negative Perfective | əlmidutif | əlmedutef | əlmedotef | əlmedolem |

| Future | -- | əlmădutăf | -- | -- |

Verb phrases are built with verb morphology, pronominal and deictic clitics, pre-verbal particles, and auxiliary elements. The pre-verbal particles are ad, wər, and their variants, which correspond to the meanings of "non-realized" and "negative" respectively.[132]

Many Berber languages have lost use of their original numerals from three onwards due to the influence of Arabic; Tarifit has lost all except one. Languages that may retain all their original numerals include Tashelhiyt, Tuareg, Ghadames, Ouargla, and Zenaga.[133][134]

Original Berber numerals agree in gender with the noun they describe, whereas the borrowed Arabic forms do not.[133][134]

The numerals 1–10 in Tashelhiyt and Mali Tuareg are as follows:[135][136][134]

| Tashelhiyt | Mali Tuareg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| masculine | feminine | masculine | feminine | |

| 1 | yan | yat | iyăn | iyăt |

| 2 | sin | snat | əssin | sănatăt |

| 3 | kraḍ | kraṭṭ | kăraḍ | kăraḍăt |

| 4 | kkuẓ | kkuẓt | akkoẓ | ăkkoẓăt |

| 5 | smmus | smmust | sămmos | sămmosăt |

| 6 | sḍis | sḍist | səḍis | səḍisăt |

| 7 | sa | sat | ăssa | ăssayăt |

| 8 | tam | tamt | ăttam | ăttamăt |

| 9 | tẓa | tẓat | tăẓẓa | tăẓẓayăt |

| 10 | mraw | mrawt | măraw | mărawăt |

Sentences in Berber languages can be divided into verbal and non-verbal sentences. The topic, which has a unique intonation in the sentence, precedes all other arguments in both types.[17]

Verbal sentences have a finite verb, and are commonly understood to follow verb–subject–object word order (VSO).[17][18] Some linguists have proposed opposing analyses of the word order patterns in Berber languages, and there has been some support for characterizing Taqbaylit as discourse-configurational.[18]

Existential, attributive, and locational sentences in most Berber languages are expressed with non-verbal sentences, which have no finite verb. In these sentences, the predicate follows the noun, with the predicative particle d sometimes in between. Two examples, one without and one with a subject, are given from Kabyle as follows:[17]

ð

PRED

a-qšiš

EL:M-boy

"It is a boy." (Kabyle)

nətta

he

ð

PRED

a-qšiš

EL:M-boy

"He is a boy." (Kabyle)

Non-verbal sentences may use the verb meaning "to be," which exists in all Berber languages. An example from Tarifit is given as follows:[17]

i-tiři

3SG:M-be:I

ða

here

"He is always here." (habitual) (Tarifit)

Above all in the area of basic lexicon, the Berber languages are very similar.[citation needed] However, the household-related vocabulary in sedentary tribes is especially different from the one found in nomadic ones: whereas Tahaggart has only two or three designations for species of palm tree, other languages may have as many as 200 similar words.[137] In contrast, Tahaggart has a rich vocabulary for the description of camels.[138]

Some loanwords in the Berber languages can be traced to pre-Roman times. The Berber words te-ḇăyne "date" and a-sḇan "loose woody tissue around the palm tree stem" originate from Ancient Egyptian, likely due to the introduction of date palm cultivation into North Africa from Egypt.[139] Around a dozen Berber words are probable Phoenician-Punic loanwords, although the overall influence of Phoenician-Punic on Berber languages is negligible.[140] A number of loanwords could be attributed to Phoenician-Punic, Hebrew, or Aramaic. The similar vocabulary between these Semitic languages, as well as Arabic, is a complicating factor in tracing the etymology of certain words.[141]

Words of Latin origin have been introduced into Berber languages over time. Maarten Kossman separates Latin loanwords in Berber languages into those from during the Roman empire ("Latin loans"), from after the fall of the Roman empire ("African Romance loans"), precolonial non-African Romance loans, and colonial and post-colonial Romance loans. It can be difficult to distinguish Latin from African Romance loans.[142] There are about 40 likely Latin or African Romance loanwords in Berber languages, which tend to be agricultural terms, religious terms, terms related to learning, or words for plants or useful objects.[142][143] Use of these terms varies by language. For example, Tuareg does not retain the Latin agricultural terms, which relate to a form of agriculture not practiced by the Tuareg people. There are some Latin loans that are only known to be used in Shawiya.[143]

The Berber calendar uses month names derived from the Julian calendar. Not every language uses every month. For example, Figuig appears to use only eight of the months.[143] These names may be precolonial non-African Romance loans, adopted into Berber languages through Arabic, rather than from Latin directly.[144]

The most influential external language on the lexicon of Berber languages is Arabic. Maarten Kossmann calculates that 0-5% of Ghadames and Awdjila's core vocabularies, and over 15% of Ghomara, Siwa, and Senhadja de Sraïr's core vocabularies, are loans from Arabic. Most other Berber languages loan from 6–15% of their core vocabulary from Arabic.[145] Salem Chaker estimates that Arabic loanwords represent 38% of Kabyle vocabulary, 25% of Tashelhiyt vocabulary, and 5% of Tuareg vocabulary, including non-core words.[146][147]

On the one hand, the words and expressions connected to Islam were borrowed, e.g. Tashlhiyt bismillah "in the name of Allah" < Classical Arabic bi-smi-llāhi, Tuareg ta-mejjīda "mosque" (Arabic masjid); on the other, Berber adopted cultural concepts such as Kabyle ssuq "market" from Arabic as-sūq, tamdint "town" < Arabic madīna. Even expressions such as the Arabic greeting as-salāmu ʿalaikum "Peace be upon you!" were adopted (Tuareg salāmu ɣlīkum).[148]

The Berber languages have influenced local Arabic dialects in the Maghreb. Although Maghrebi Arabic has a predominantly Semitic and Arabic vocabulary,[149] it contains a few Berber loanwords which represent 2–3% of the vocabulary of Libyan Arabic, 8–9% of Algerian Arabic and Tunisian Arabic, and 10–15% of Moroccan Arabic.[150] Their influence is also seen in some languages in West Africa. F. W. H. Migeod pointed to strong resemblances between Berber and Hausa in such words and phrases as these:

| Berber | Hausa | gloss |

|---|---|---|

| obanis | obansa | his father |

| a bat | ya bata | he was lost |

| eghare | ya kirra | he called |

In addition he notes that the genitive in both languages is formed with n = "of" (though likely a common inheritance from Proto-Afro-Asiatic; cf. A.Eg genitive n).[151]

A number of extinct populations are believed to have spoken Afro-Asiatic languages of the Berber branch. According to Peter Behrens (1981) and Marianne Bechaus-Gerst (2000), linguistic evidence suggests that the peoples of the C-Group culture in present-day southern Egypt and northern Sudan spoke Berber languages.[47][48] The Nilo-Saharan Nobiin language today contains a number of key pastoralism related loanwords that are of Berber origin, including the terms for sheep and water/Nile. This in turn suggests that the C-Group population—which, along with the Kerma culture, inhabited the Nile valley immediately before the arrival of the first Nubian speakers—spoke Afro-Asiatic languages.[47]

Additionally, historical linguistics indicate that the Guanche language, which was spoken on the Canary Islands by the ancient Guanches, likely belonged to the Berber branch of the Afro-Asiatic family.[152]

Most languages of the Berber branch are mutually unintelligible.

By [the 14th century], however, the Berbers were in retreat, subjected to Arabization of two very different kinds. The predominance of written Arabic had ended the writing of Amazigh (Berber) languages in both the old Libyan and the new Arabic script, reducing its languages to folk languages.[In other words, Tamazight had earlier been the dominant spoken and written language of the Imazighen.]

The contribution of autochthonous North African populations in Carthaginian history is obscured by the use of terms like 'Western Phoenicians', and even to an extent, 'Punic', in the literature to refer to Carthaginians, as it implies a primarily colonial population and diminishes indigenous involvement in the Carthaginian Empire. As a result, the role of autochthonous populations has been largely overlooked in studies of Carthage and its empire. Genetic approaches are well suited to examine such assumptions, and here we show that North African populations contributed substantially to the genetic makeup of Carthaginian cities.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Amazigh arts, like the Tamazight language, have coexisted with other North African forms of expression since pre-Islamic times.[emphasis added]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link)

Most Berber languages have a high percentage of borrowing from Arabic, as well as from other languages.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Tamazight in Morocco is divided by linguists into three major dialect areas usually referred to as: Taselhit in the south, Tamazight in the Middle Atlas mountains, and Tarifit in the north.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Les chiffres se rapportent, non pas au dernier recensement, celui de 1911, mais au précédenl, celui de 1906. C'est le seul sur lequel on avait, et même on a encore maintenant, des données suffisantes. Voici ces chiffres. Sur une population indigène totale de 4 447 149 hab., nous trouvons 1 305 730 berbérophones; c'est un peu moins du tiers.

{{cite book}}: |website= ignored (help)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

The Berber languages do not diverge from this trend, as no sonority restriction is imposed on their consonant clusters. Word-initial CC may consist of a sequence of stops or obstruent-sonorant, each with their mirror-image.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Zavadovskij gives statistics for the percentage of Berber words in North African Muslim Arabic dialects: 10–15 percent Berber components in the Moroccan Arabic lexicon, 8–9 percent in Algerian and Tunisian Arabic, and only 2–3 percent in Libyan Arabic.