Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

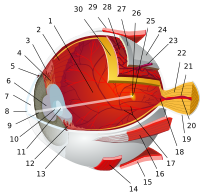

| Retinal ganglion cell | |

|---|---|

Diagram showing cross-section of retinal layers. The area labeled "Ganglionic layer" contains retinal ganglion cells | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D012165 |

| NeuroLex ID | nifext_17 |

| FMA | 67765 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

A retinal ganglion cell (RGC) is a type of neuron located near the inner surface (the ganglion cell layer) of the retina of the eye. It receives visual information from photoreceptors via two intermediate neuron types: bipolar cells and retina amacrine cells. Retina amacrine cells, particularly narrow field cells, are important for creating functional subunits within the ganglion cell layer and making it so that ganglion cells can observe a small dot moving a small distance.[1] Retinal ganglion cells collectively transmit image-forming and non-image forming visual information from the retina in the form of action potential to several regions in the thalamus, hypothalamus, and mesencephalon, or midbrain.

Retinal ganglion cells vary significantly in terms of their size, connections, and responses to visual stimulation but they all share the defining property of having a long axon that extends into the brain. These axons form the optic nerve, optic chiasm, and optic tract.

A small percentage of retinal ganglion cells contribute little or nothing to vision, but are themselves photosensitive; their axons form the retinohypothalamic tract and contribute to circadian rhythms and pupillary light reflex, the resizing of the pupil.

Function

There are about 0.7 to 1.5 million retinal ganglion cells in the human retina.[2] With about 4.6 million cone cells and 92 million rod cells, or 96.6 million photoreceptors per retina,[3] on average each retinal ganglion cell receives inputs from about 100 rods and cones. However, these numbers vary greatly among individuals and as a function of retinal location. In the fovea (center of the retina), a single ganglion cell will communicate with as few as five photoreceptors. In the extreme periphery (edge of the retina), a single ganglion cell will receive information from many thousands of photoreceptors.[citation needed]

Retinal ganglion cells spontaneously fire action potentials at a base rate while at rest. Excitation of retinal ganglion cells results in an increased firing rate while inhibition results in a depressed rate of firing.

Types

There is wide variability in ganglion cell types across species. In primates, including humans, there are generally three classes of RGCs:

- W-ganglion: small, 40% of total, broad fields in retina, excitation from rods. Detection of direction movement anywhere in the field.

- X-ganglion: medium diameter, 55% of total, small field, color vision. Sustained response.

- Y-ganglion: largest, 5%, very broad dendritic field, respond to rapid eye movement or rapid change in light intensity. Transient response.

The W, X and Y retinal ganglion types arose from studies of the cat.[4][5][6] These physiological types are closely related to the respective morphological retinal ganglion types , and .[5]: 416

Based on their projections and functions, there are at least five main classes of retinal ganglion cells:

- Midget cell (parvocellular/P pathway; P cells)

- Parasol cell (magnocellular/M pathway; M cells)

- Bistratified cell (koniocellular/K pathway; K cells)

- Photosensitive ganglion cells

- Other ganglion cells projecting to the superior colliculus for eye movements (saccades)[7]

P-type

P-type retinal ganglion cells project to the parvocellular layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus. These cells are known as midget retinal ganglion cells, based on the small sizes of their dendritic trees and cell bodies. About 80% of all retinal ganglion cells are midget cells in the parvocellular pathway. They receive inputs from relatively few rods and cones. They have slow conduction velocity, and respond to changes in color but respond only weakly to changes in contrast unless the change is great. They have simple center-surround receptive fields, where the center may be either ON or OFF while the surround is the opposite.

M-type

M-type retinal ganglion cells project to the magnocellular layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus. These cells are known as parasol retinal ganglion cells, based on the large sizes of their dendritic trees and cell bodies. About 10% of all retinal ganglion cells are parasol cells, and these cells are part of the magnocellular pathway. They receive inputs from relatively many rods and cones. They have fast conduction velocity, and can respond to low-contrast stimuli, but are not very sensitive to changes in color. They have much larger receptive fields which are nonetheless also center-surround.

K-type

BiK-type retinal ganglion cells project to the koniocellular layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus. K-type retinal ganglion cells have been identified only relatively recently. Koniocellular means "cells as small as dust"; their small size made them hard to find. About 10% of all retinal ganglion cells are bistratified cells, and these cells go through the koniocellular pathway. They receive inputs from intermediate numbers of rods and cones. They may be involved in color vision. They have very large receptive fields that only have centers (no surrounds) and are always ON to the blue cone and OFF to both the red and green cone.

Photosensitive ganglion cell

Photosensitive ganglion cells, including but not limited to the giant retinal ganglion cells, contain their own photopigment, melanopsin, which makes them respond directly to light even in the absence of rods and cones. They project to, among other areas, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) via the retinohypothalamic tract for setting and maintaining circadian rhythms. Other retinal ganglion cells projecting to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) include cells making connections with the Edinger-Westphal nucleus (EW), for control of the pupillary light reflex, and giant retinal ganglion cells.

Physiology

Most mature ganglion cells are able to fire action potentials at a high frequency because of their expression of Kv3 potassium channels.[9][10][11]

Pathology

Degeneration of axons of the retinal ganglion cells (the optic nerve) is a hallmark of glaucoma.[12]

Developmental biology

Retinal growth: the beginning

Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are born between embryonic day 11 and post-natal day zero in the mouse and between week 5 and week 18 in utero in human development.[13][14][15] In mammals, RGCs are typically added at the beginning in the dorsal central aspect of the optic cup, or eye primordium. Then RC growth sweeps out ventrally and peripherally from there in a wave-like pattern.[16] This process depends on a host of factors, ranging from signaling factors like FGF3 and FGF8 to proper inhibition of the Notch signaling pathway. Most importantly, the bHLH (basic helix-loop-helix)-domain containing transcription factor Atoh7 and its downstream effectors, such as Brn3b and Isl-1, work to promote RGC survival and differentiation.[13] The "differentiation wave" that drives RGC development across the retina is also regulated in particular of the bHLH factors Neurog2 and Ascl1 and FGF/Shh signaling, deriving from the periphery.[13][16][17]

Growth within the retinal ganglion cell (optic fiber) layer

Early progenitor RGCs will typically extend processes connecting to the inner and outer limiting membranes of the retina with the outer layer adjacent to the retinal pigment epithelium and inner adjacent to the future vitreous humor. The cell soma will pull towards the pigment epithelium, undergo a terminal cell division and differentiation, and then migrate backwards towards the inner limiting membrane in a process called somal translocation. The kinetics of RGC somal translocation and underlying mechanisms are best understood in the zebrafish.[18] The RGC will then extend an axon in the retinal ganglion cell layer, which is directed by laminin contact.[19] The retraction of the apical process of the RGC is likely mediated by Slit–Robo signaling.[13]

RGCs will grow along glial end feet positioned on the inner surface (side closest to the future vitreous humor). Neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) will mediate this attachment via homophilic interactions between molecules of like isoforms (A or B). Slit signaling also plays a role, preventing RGCs from growing into layers beyond the optic fiber layer.[20]

Axons from the RGCs will grow and extend towards the optic disc, where they exit the eye. Once differentiated, they are bordered by an inhibitory peripheral region and a central attractive region, thus promoting extension of the axon towards the optic disc. CSPGs exist along the retinal neuroepithelium (surface over which the RGCs lie) in a peripheral high–central low gradient.[13] Slit is also expressed in a similar pattern, secreted from the cells in the lens.[20] Adhesion molecules, like N-CAM and L1, will promote growth centrally and will also help to properly fasciculate (bundle) the RGC axons together. Shh is expressed in a high central, low peripheral gradient, promoting central-projecting RGC axons extension via Patched-1, the principal receptor for Shh, mediated signaling.[21]

Growth into and through the optic nerve

RGCs exit the retinal ganglion cell layer through the optic disc, which requires a 45° turn.[13] This requires complex interactions with optic disc glial cells which will express local gradients of Netrin-1, a morphogen that will interact with the Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC) receptor on growth cones of the RGC axon. This morphogen initially attracts RGC axons, but then, through an internal change in the growth cone of the RGC, netrin-1 becomes repulsive, pushing the axon away from the optic disc.[22] This is mediated through a cAMP-dependent mechanism. Additionally, CSPGs and Eph–ephrin signaling may also be involved.

RGCs will grow along glial cell end feet in the optic nerve. These glia will secrete repulsive semaphorin 5a and Slit in a surround fashion, covering the optic nerve which ensures that they remain in the optic nerve. Vax1, a transcription factor, is expressed by the ventral diencephalon and glial cells in the region where the chiasm is formed, and it may also be secreted to control chiasm formation.[23]

Growth at the optic chiasm

When RGCs approach the optic chiasm, the point at which the two optic nerves meet, at the ventral diencephalon around embryonic days 10–11 in the mouse, they have to make the decision to cross to the contralateral optic tract or remain in the ipsilateral optic tract. In the mouse, about 5% of RGCs, mostly those coming from the ventral-temporal crescent (VTc) region of the retina, will remain ipsilateral, while the remaining 95% of RGCs will cross.[13] This is largely controlled by the degree of binocular overlap between the two fields of sight in both eyes. Mice do not have a significant overlap, whereas, humans, who do, will have about 50% of RGCs cross and 50% will remain ipsilateral.

Building the repulsive outline of the chiasm

Once RGCs reach the chiasm, the glial cells supporting them will change from an intrafascicular to radial morphology. A group of diencephalic cells that express the cell surface antigen stage-specific embryonic antigen (SSEA)-1 and CD44 will form an inverted V-shape.[24] They will establish the posterior aspect of the optic chiasm border. Additionally, Slit signaling is important here: Heparin sulfate proteoglycans, proteins in the ECM, will anchor the Slit morphogen at specific points in the posterior chiasm border.[25] RGCs will begin to express Robo, the receptor for Slit, at this point, thus facilitating the repulsion.

Contralateral projecting RGCs

RGC axons traveling to the contralateral optic tract need to cross. Shh, expressed along the midline in the ventral diencephalon, provides a repulsive cue to prevent RGCs from crossing the midline ectopically. However, a hole is generated in this gradient, thus allowing RGCs to cross.

Molecules mediating attraction include NrCAM, which is expressed by growing RGCs and the midline glia and acts along with Sema6D, mediated via the plexin-A1 receptor.[13] VEGF-A is released from the midline directs RGCs to take a contralateral path, mediated by the neuropilin-1 (NRP1) receptor.[26] cAMP seems to be very important in regulating the production of NRP1 protein, thus regulating the growth cones response to the VEGF-A gradient in the chiasm.[27]

Ipsilateral projecting RGCs

The only component in mice projecting ipsilaterally are RGCs from the ventral-temporal crescent in the retina, and only because they express the Zic2 transcription factor. Zic2 will promote the expression of the tyrosine kinase receptor EphB1, which, through forward signaling (see review by Xu et al.[28]) will bind to ligand ephrin B2 expressed by midline glia and be repelled to turn away from the chiasm. Some VTc RGCs will project contralaterally because they express the transcription factor Islet-2, which is a negative regulator of Zic2 production.[29]

Shh plays a key role in keeping RGC axons ipsilateral as well. Shh is expressed by the contralaterally projecting RGCs and midline glial cells. Boc, or Brother of CDO (CAM-related/downregulated by oncogenes), a co-receptor for Shh that influences Shh signaling through Ptch1,[30] seems to mediate this repulsion, as it is only on growth cones coming from the ipsilaterally projecting RGCs.[21]

Other factors influencing ipsilateral RGC growth include the Teneurin family, which are transmembrane adhesion proteins that use homophilic interactions to control guidance, and Nogo, which is expressed by midline radial glia.[31][32] The Nogo receptor is only expressed by VTc RGCs.[13]

Finally, other transcription factors seem to play a significant role in altering. For example, Foxg1, also called Brain-Factor 1, and Foxd1, also called Brain Factor 2, are winged-helix transcription factors that are expressed in the nasal and temporal optic cups and the optic vesicles begin to evaginate from the neural tube. These factors are also expressed in the ventral diencephalon, with Foxd1 expressed near the chiasm, while Foxg1 is expressed more rostrally. They appear to play a role in defining the ipsilateral projection by altering expression of Zic2 and EphB1 receptor production.[13][33]

Growth in the optic tract

Once out of the optic chiasm, RGCs will extend dorsocaudally along the ventral diencephalic surface making the optic tract, which will guide them to the superior colliculus and lateral geniculate nucleus in the mammals, or the tectum in lower vertebrates.[13] Sema3d seems to be promote growth, at least in the proximal optic tract, and cytoskeletal re-arrangements at the level of the growth cone appear to be significant.[34]

Myelination

In most mammals, the axons of retinal ganglion cells are not myelinated where they pass through the retina. However, the parts of axons that are beyond the retina, are myelinated. This myelination pattern is functionally explained by the relatively high opacity of myelin—myelinated axons passing over the retina would absorb some of the light before it reaches the photoreceptor layer, reducing the quality of vision. There are human eye diseases where this does, in fact, happen. In some vertebrates, such as the chicken, the ganglion cell axons are myelinated inside the retina.[35]

See also

References

- ^ Masland RH (January 2012). "The tasks of amacrine cells". Visual Neuroscience. 29 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1017/s0952523811000344. PMC 3652807. PMID 22416289.

- ^ Watson AB (June 2014). "A formula for human retinal ganglion cell receptive field density as a function of visual field location" (PDF). Journal of Vision. 14 (7): 15. doi:10.1167/14.7.15. PMID 24982468.

- ^ Curcio CA, Sloan KR, Kalina RE, Hendrickson AE (February 1990). "Human photoreceptor topography" (PDF). The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 292 (4): 497–523. doi:10.1002/cne.902920402. PMID 2324310. S2CID 24649779.

- ^ Christina Enroth-Cugell; J. G. Robson (1966). "The Contrast Sensitivity of Retinal Ganglion Cells of the Cat". Journal of Physiology. 187 (3): 517–552. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008107. PMC 1395960. PMID 16783910.

- ^ a b Boycott, Brian Blundell; Wässle, H. (1974). "The morphological types of ganglion cells of the domestic cat's retina". The Journal of Physiology. 240 (2): 397–419. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010616. PMC 1331022. PMID 4422168.

- ^ Jones, Edward G (1985). The Thalamus. New York: Springer. pp. 487–508. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1749-8. ISBN 978-1-4613-5704-9. S2CID 41337319.

- ^ Principles of Neural Science 4th Ed. Kandel et al.

- ^ a b c Schottdorf M, Lee BB (June 2021). "A quantitative description of macaque ganglion cell responses to natural scenes: the interplay of time and space". The Journal of Physiology. 599 (12): 3169–3193. doi:10.1113/JP281200. PMC 8998785. PMID 33913164. S2CID 233448275.

- ^ "Ionic conductances underlying excitability in tonically firing retinal ganglion cells of adult rat".

- ^ Henne J, Pöttering S, Jeserich G (December 2000). "Voltage-gated potassium channels in retinal ganglion cells of trout: a combined biophysical, pharmacological, and single-cell RT-PCR approach". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 62 (5): 629–37. doi:10.1002/1097-4547(20001201)62:5<629::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 11104501. S2CID 44513007.

- ^ Henne J, Jeserich G (January 2004). "Maturation of spiking activity in trout retinal ganglion cells coincides with upregulation of Kv3.1- and BK-related potassium channels". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 75 (1): 44–54. doi:10.1002/jnr.10830. PMID 14689447. S2CID 38851244.

- ^ Jadeja RN, Thounaojam MC, Martin PM (2020). "Implications of NAD + Metabolism in the Aging Retina and Retinal Degeneration". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2020: 2692794. doi:10.1155/2020/2692794. PMC 7238357. PMID 32454935.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Erskine L, Herrera E (2014-01-01). "Connecting the retina to the brain". ASN Neuro. 6 (6): 175909141456210. doi:10.1177/1759091414562107. PMC 4720220. PMID 25504540.

- ^ Petros TJ, Rebsam A, Mason CA (2008-01-01). "Retinal axon growth at the optic chiasm: to cross or not to cross". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 31: 295–315. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125609. PMID 18558857.

- ^ Pacal M, Bremner R (May 2014). "Induction of the ganglion cell differentiation program in human retinal progenitors before cell cycle exit". Developmental Dynamics. 243 (5): 712–29. doi:10.1002/dvdy.24103. PMID 24339342. S2CID 4133348.

- ^ a b Hufnagel RB, Le TT, Riesenberg AL, Brown NL (April 2010). "Neurog2 controls the leading edge of neurogenesis in the mammalian retina". Developmental Biology. 340 (2): 490–503. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.002. PMC 2854206. PMID 20144606.

- ^ Lo Giudice Q, Leleu M, La Manno G, Fabre PJ (September 2019). "Single-cell transcriptional logic of cell-fate specification and axon guidance in early-born retinal neurons". Development. 146 (17): dev178103. doi:10.1242/dev.178103. PMID 31399471.

- ^ Icha J, Kunath C, Rocha-Martins M, Norden C (October 2016). "Independent modes of ganglion cell translocation ensure correct lamination of the zebrafish retina". The Journal of Cell Biology. 215 (2): 259–275. doi:10.1083/jcb.201604095. PMC 5084647. PMID 27810916.

- ^ Randlett O, Poggi L, Zolessi FR, Harris WA (April 2011). "The oriented emergence of axons from retinal ganglion cells is directed by laminin contact in vivo". Neuron. 70 (2): 266–80. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.013. PMC 3087191. PMID 21521613.

- ^ a b Thompson H, Andrews W, Parnavelas JG, Erskine L (November 2009). "Robo2 is required for Slit-mediated intraretinal axon guidance". Developmental Biology. 335 (2): 418–26. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.034. PMC 2814049. PMID 19782674.

- ^ a b Sánchez-Camacho C, Bovolenta P (November 2008). "Autonomous and non-autonomous Shh signalling mediate the in vivo growth and guidance of mouse retinal ganglion cell axons". Development. 135 (21): 3531–41. doi:10.1242/dev.023663. PMID 18832395.

- ^ Höpker VH, Shewan D, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M, Holt C (September 1999). "Growth-cone attraction to netrin-1 is converted to repulsion by laminin-1". Nature. 401 (6748): 69–73. Bibcode:1999Natur.401...69H. doi:10.1038/43441. PMID 10485706. S2CID 205033254.

- ^ Kim N, Min KW, Kang KH, Lee EJ, Kim HT, Moon K, et al. (September 2014). "Regulation of retinal axon growth by secreted Vax1 homeodomain protein". eLife. 3: e02671. doi:10.7554/eLife.02671. PMC 4178304. PMID 25201875.

- ^ Sretavan DW, Feng L, Puré E, Reichardt LF (May 1994). "Embryonic neurons of the developing optic chiasm express L1 and CD44, cell surface molecules with opposing effects on retinal axon growth". Neuron. 12 (5): 957–75. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(94)90307-7. PMC 2711898. PMID 7514428.

- ^ Wright KM, Lyon KA, Leung H, Leahy DJ, Ma L, Ginty DD (December 2012). "Dystroglycan organizes axon guidance cue localization and axonal pathfinding". Neuron. 76 (5): 931–44. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.009. PMC 3526105. PMID 23217742.

- ^ Erskine L, Reijntjes S, Pratt T, Denti L, Schwarz Q, Vieira JM, et al. (June 2011). "VEGF signaling through neuropilin 1 guides commissural axon crossing at the optic chiasm". Neuron. 70 (5): 951–65. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.052. PMC 3114076. PMID 21658587.

- ^ Dell AL, Fried-Cassorla E, Xu H, Raper JA (July 2013). "cAMP-induced expression of neuropilin1 promotes retinal axon crossing in the zebrafish optic chiasm". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (27): 11076–88. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0197-13.2013. PMC 3719991. PMID 23825413.

- ^ Xu NJ, Henkemeyer M (February 2012). "Ephrin reverse signaling in axon guidance and synaptogenesis". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 23 (1): 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.024. PMC 3288821. PMID 22044884.

- ^ Pak W, Hindges R, Lim YS, Pfaff SL, O'Leary DD (November 2004). "Magnitude of binocular vision controlled by islet-2 repression of a genetic program that specifies laterality of retinal axon pathfinding". Cell. 119 (4): 567–78. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.026. PMID 15537545. S2CID 16663526.

- ^ Allen BL, Song JY, Izzi L, Althaus IW, Kang JS, Charron F, et al. (June 2011). "Overlapping roles and collective requirement for the coreceptors GAS1, CDO, and BOC in SHH pathway function". Developmental Cell. 20 (6): 775–87. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.018. PMC 3121104. PMID 21664576.

- ^ Wang J, Chan CK, Taylor JS, Chan SO (June 2008). "Localization of Nogo and its receptor in the optic pathway of mouse embryos". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 86 (8): 1721–33. doi:10.1002/jnr.21626. PMID 18214994. S2CID 25123173.

- ^ Kenzelmann D, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Leachman NT, Tucker RP (March 2008). "Teneurin-1 is expressed in interconnected regions of the developing brain and is processed in vivo". BMC Developmental Biology. 8: 30. doi:10.1186/1471-213X-8-30. PMC 2289808. PMID 18366734.

- ^ Herrera E, Marcus R, Li S, Williams SE, Erskine L, Lai E, Mason C (November 2004). "Foxd1 is required for proper formation of the optic chiasm". Development. 131 (22): 5727–39. doi:10.1242/dev.01431. PMID 15509772.

- ^ Sakai JA, Halloran MC (March 2006). "Semaphorin 3d guides laterality of retinal ganglion cell projections in zebrafish". Development. 133 (6): 1035–44. doi:10.1242/dev.02272. PMID 16467361.

- ^ Villegas GM (July 1960). "Electron microscopic study of the vertebrate retina". The Journal of General Physiology. 43(6)Suppl (6): 15–43. doi:10.1085/jgp.43.6.15. PMC 2195075. PMID 13842313.