Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

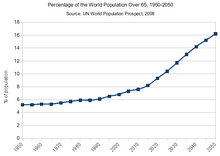

Population ageing is an increasing median age in a population because of declining fertility rates and rising life expectancy. Most countries have rising life expectancy and an ageing population, trends that emerged first in developed countries but are now seen in virtually all developing countries. In most developed countries, the phenomenon of population aging began to gradually emerge in the late 19th century. The aging of the world population occurred in the late 20th century, with the proportion of people aged 65 and above accounting for 6% of the total population. This reflects the overall decline in the world's fertility rate at that time.[1] That is the case for every country in the world except the 18 countries designated as "demographic outliers" by the United Nations.[2][failed verification] The aged population is currently at its highest level in human history.[3] The UN predicts the rate of population ageing in the 21st century will exceed that of the previous century.[3] The number of people aged 60 years and over has tripled since 1950 and reached 600 million in 2000 and surpassed 700 million in 2006. It is projected that the combined senior and geriatric population will reach 2.1 billion by 2050.[4][5] Countries vary significantly in terms of the degree and pace of ageing, and the UN expects populations that began ageing later will have less time to adapt to its implications.[3]

Overview

Population ageing is a shift in the distribution of a country's population towards older ages and is usually reflected in an increase in the population's mean and median ages, a decline in the proportion of the population composed of children, and a rise in the proportion of the population composed of the elderly. Population ageing is widespread across the world and is most advanced in the most highly developed countries, but it is growing faster in less developed regions, which means that older persons will be increasingly concentrated in the less developed regions of the world.[6] The Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, however, concluded that population ageing has slowed considerably in Europe and will have the greatest future impact in Asia, especially since Asia is in stage five (very low birth rate and low death rate) of the demographic transition model.[7]

Among the countries currently classified by the United Nations as more developed (with a total population of 1.2 billion in 2005), the overall median age rose from 28 in 1950 to 40 in 2010 and is forecast to rise to 44 by 2050. The corresponding figures for the world as a whole are 24 in 1950, 29 in 2010, and 36 in 2050. For the less developed regions, the median age will go from 26 in 2010 to 35 in 2050.[8]

Population ageing arises from two possibly-related demographic effects: increasing longevity and declining fertility. An increase in longevity raises the average age of the population by increasing the numbers of surviving older people. A decline in fertility reduces the number of babies, and as the effect continues, the numbers of younger people in general also reduce. Of the two forces, declining fertility now contributes to most of the population ageing in the world.[9] More specifically, the large decline in the overall fertility rate over the last half-century is primarily responsible for the population ageing in the world's most developed countries. Because many developing countries are going through faster fertility transitions, they will experience even faster population ageing than the currently-developed countries will.

The rate at which the population ages is likely to increase over the next three decades;[10] however, few countries know whether their older population are living the extra years of life in good or poor health. A "compression of morbidity" would imply reduced disability in old age,[11] but an expansion would see an increase in poor health with increased longevity. Another option has been posed for a situation of "dynamic equilibrium."[12] That is crucial information for governments if the limits of lifespan continue to increase indefinitely, as some researchers believe.[13] The World Health Organization's suite of household health studies is working to provide the needed health and well-being evidence, such as the World Health Survey,[14] and the Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). The surveys cover 308,000 respondents aged at least 18 and 81,000 aged at least 50 from 70 countries.

The Global Ageing Survey, exploring attitudes, expectations, and behaviours towards later life and retirement, directed by George Leeson, and covering 44,000 people aged 40–80 in 24 countries from across the globe, has revealed that many people are now fully aware of the ageing of the world's population and the implications that it will have on their lives and those of their children and grandchildren.

Canada has the highest per capita immigration rate in the world, partly to counter population ageing. The C. D. Howe Institute, a conservative think tank, has suggested that immigration cannot be used as a viable means to counter population ageing.[15] That conclusion is also seen in the work of other scholars. The demographers Peter McDonald and Rebecca Kippen commented, "As fertility sinks further below replacement level, increasingly higher levels of annual net migration will be required to maintain a target of even zero population growth."[16]

Around the world

The world's older population is growing dramatically.[17]

The more developed countries also have older populations as their citizens live longer. Less developed countries have much younger populations. An interactive version of the map is available here. Asia and Africa are the two regions with a significant number of countries facing population ageing. Within 20 years, many countries in those regions will face a situation of the largest population cohort being those over 65 and the average age approaching 50. In 2100, according to research led by the University of Washington, 2.4 billion people will be over the age of 65, compared with 1.7 billion under the age of 20.[18] The Oxford Institute of Population Ageing is an institution looking at global population ageing. Its research reveals that many of the views of global ageing are based on myths and that there will be considerable opportunities for the world as its population matures, as the Institute's director, Professor Sarah Harper, highlighted in her book Ageing Societies.

Most of the developed countries now have sub-replacement fertility levels, and population growth now depends largely on immigration together with population momentum, which also arises from previous large generations now enjoying longer life expectancy.

Of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds, 100,000 per day, die of age-related causes.[19] In industrialised nations, that proportion is much higher and reaches 90%.[19]

Well-being and social policies

The economic effects of an ageing population are considerable.[20] Nowadays, more and more people are paying attention to the economic issues and social policy challenges related to the elderly population.[21] Older people have higher accumulated savings per head than younger people but spend less on consumer goods. Depending on the age ranges at which the changes occur, an ageing population may thus result in lower interest rates and the economic benefits of lower inflation. Some economists[who?] in Japan see advantages in such changes, notably the opportunity to progress automation and technological development without causing unemployment, and emphasise a shift from GDP to personal well-being.

However, population ageing also increases some categories of expenditure, including some met from public finances. The largest area of expenditure in many countries is now health care, whose cost is likely to increase dramatically as populations age. This would present governments with hard choices between higher taxes, including a possible reweighing of tax from earnings to consumption and a reduced government role in providing health care.The working population will face greater pressure, and a portion of their taxes will have to be used to pay for healthcare and pensions for the elderly.[citation needed] However, recent studies in some countries demonstrate the dramatic rising costs of health care are more attributable to rising drug and doctor costs and the higher use of diagnostic testing by all age groups, not to the ageing population that is often claimed.[22][23][24]

The second-largest expenditure of most governments is education, with expenses that tend to fall with an ageing population, especially as fewer young people would probably continue into tertiary education as they would be in demand as part of the work force.

Social security systems have also begun to experience problems. Earlier defined benefit pension systems are experiencing sustainability problems because of the increased longevity. The extension of the pension period was not paired with an extension of the active labour period or a rise in pension contributions, which has resulted in a decline of replacement ratios.

Population ageing also affects workforce. In many countries, the increase in the number of elderly people means the weakening or disappearance of the "demographic dividend", and social resources have to flow more towards elderly people in need of support.[25] The demographic dividend refers to the beneficial impact of a decline in fertility rate on a country's population age structure and economic growth.[26] The older workers would spend more time on work and human capital of an ageing workforce is low, reducing labor productivity.[27]

The expectation of continuing population ageing prompts questions about welfare states' capacity to meet the needs of the population. In the early 2000s, the World Health Organization set up guidelines to encourage "active ageing" and to help local governments address the challenges of an ageing population (Global Age-Friendly Cities) with regard to urbanization, housing, transportation, social participation, health services, etc.[28] Local governments are well positioned to meet the needs of local, smaller populations, but as their resources vary from one to another (e.g. property taxes, the existence of community organizations), the greater responsibility on local governments is likely to increase inequalities.[29][30][31] In Canada, the most fortunate and healthier elders tend to live in more prosperous cities offering a wide range of services, but the less fortunate lack access to the same level of resources.[32] Private residences for the elderly also provide many services related to health and social participation (e.g. pharmacy, group activities, and events) on site, but they are not accessible to the less fortunate.[33] Also, the environmental gerontology indicates the importance of the environment in active ageing.[34][35][36] In fact, promoting good environments (natural, built, social) in ageing can improve health and quality of life and reduce the problems of disability and dependence, and, in general, social spending and health spending.[37]

An ageing population may provide incentive for technological progress, as some hypothesise the effect of a shrinking workforce may be offset by automation and productivity gains.

Meanwhile, improving the productivity of the elderly has also become a method to alleviate the problem of social aging. But this first requires increasing their investment in education, and providing suitable job opportunities is equally important.[38]

Generally in West Africa and specifically in Ghana, social policy implications of demographic ageing are multidimensional (such as rural-urban distribution, gender composition, levels of literacy/illiteracy as well as their occupational histories and income security).[5] Current policies on ageing in Ghana seem to be disjointed, and ideas on documents on to improve policies in population ageing have yet to be concretely implemented,[5] perhaps partly because of many arguments that older people are only a small proportion of the population[39]

Global ageing populations seem to cause many countries to be increasing the age for old age security from 60 to 65 to decrease the cost of the scheme of the GDP.[5] However, even so, in industrialized countries with the greatest improvement in life expectancy, discussions about continuing to raise the eligibility age for pension benefits have intensified in order to reduce economic burden more significantly.[40] Age discrimination can be defined as "the systematic and institutionalized denial of the rights of older people on the basis of their age by individuals, groups, organisations, and institutions."[39] Some of the abuse can be a result of ignorance, thoughtlessness, prejudice, and stereotyping. Forms of discrimination are economic accessibility, social accessibility, temporal accessibility and administrative accessibility.[41]

In most countries worldwide, particularly countries in Africa, older people are typically the poorest members of the social spectrum and live below the poverty line.

Moreover, the growing burden of health expenditure has evolved into a social policy and cost management issue, not just a population issue.[42]

See also

- Aging

- Aging of Europe

- Aging of Japan

- Aging of the United States

- Aging of China

- Aging of South Korea

- Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR)

- Demographic transition

- Gerontology

- Overpopulation

- Political demography

- Population decline

- Senescence

- The Silver Tsunami

- List of countries and regions by population ages 65 and above

References

- ^ Uhlenberg, Peter, ed. (2009). International handbook of population aging. International handbooks of population. Dordrecht ; London: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-8355-6. OCLC 390135418.

- ^ United Nations Development Programme (September 2005). UN Human Development Report 2005, International Cooperation at a Crossroads-Aid, Trade and Security in an Unequal World (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. ISBN 978-0-19-530511-1.

- ^ a b c World Population Ageing: 1950-2050, United Nations Population Division.

- ^ Chucks, J (July 2010). "Population Ageing in Goa: Research Gaps and the Way Forward". Journal of Aging Research. 2010: 672157. doi:10.4061/2010/672157. PMC 3003962. PMID 21188229.

- ^ a b c d Issahaku, Paul; Neysmith, Sheila (2013). "Policy Implications of Population Ageing in West Africa". International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 33 (3/4): 186–202. doi:10.1108/01443331311308230.

- ^ United Nations. "World Population Ageing 2013" (PDF).

- ^ Shaban, Mostafa (2020). Dr. lambert academic publishing. ISBN 978-620-3-19697-9.

- ^ United Nations. "World Ageing Population 2013" (PDF).

- ^ Weil, David N., "The Economics of Population Aging" in Mark R. Rosenzweig and Oded Stark, eds., Handbook of Population and Family Economics, New York: Elsevier, 1997, 967-1014.

- ^ Lutz, W.; Sanderson, W.; Scherbov, S. (2008-02-07). "The coming acceleration of global population ageing". Nature. 451 (7179): 716–719. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..716L. doi:10.1038/nature06516. PMID 18204438. S2CID 4379499.

The median age of the world's population increases from 26.6 years in 2000 to 37.3 years in 2050 and then to 45.6 years in 2100, when it is not adjusted for longevity increase.

- ^ Fries, J. F. (1980-07-17). "Aging, Natural Death, and the Compression of Morbidity". The New England Journal of Medicine. 303 (3): 130–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM198007173030304. PMC 2567746. PMID 7383070.

the average age at first infirmity can be raised, thereby making the morbidity curve more rectangular.

- ^ Manton KG (1982). "Manton, 1982". Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 60 (2): 183–244. doi:10.2307/3349767. JSTOR 3349767. PMID 6919770. S2CID 45827427.

- ^ Oeppen, J.; Vaupel, J. W. (2002-05-10). "Broken Limits to Life Expectancy". Science. 296 (5570): 1029–31. doi:10.1126/science.1069675. PMID 12004104. S2CID 1132260.

- ^ "Current Status of the World Health Survey". who.int. 2011. Archived from the original on August 19, 2005. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Yvan Guillemette; William Robson (September 2006). "No Elixir of Youth" (PDF). Backgrounder. 96. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ Peter McDonald; Rebecca Kippen (2000). "Population Futures for Australia and New Zealand: An Analysis of the Options" (PDF). New Zealand Population Review. 26 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ^ "World's older population grows dramatically". National Institute on Aging. 2016-03-28. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (2020-07-15). "World population in 2100 could be 2 billion below UN forecasts, study suggests". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- ^ a b Aubrey D.N.J, de Grey (2007). "Life Span Extension Research and Public Debate: Societal Considerations" (PDF). Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology. 1 (1, Article 5). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.395.745. doi:10.2202/1941-6008.1011. S2CID 201101995. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Jarzebski, Marcin Pawel; Elmqvist, Thomas; Gasparatos, Alexandros; Fukushi, Kensuke; Eckersten, Sofia; Haase, Dagmar; Goodness, Julie; Khoshkar, Sara; Saito, Osamu; Takeuchi, Kazuhiko; Theorell, Töres; Dong, Nannan; Kasuga, Fumiko; Watanabe, Ryugo; Sioen, Giles Bruno; Yokohari, Makoto; Pu, Jian (2021). "Ageing and population shrinking: implications for sustainability in the urban century". npj Urban Sustainability. 1 (1): 17. Bibcode:2021npjUS...1...17J. doi:10.1038/s42949-021-00023-z.

- ^ Sanderson, Warren C.; Scherbov, Sergei (2007). "A new perspective on population aging". Demographic Research. 16: 27–58. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2007.16.2. ISSN 1435-9871. JSTOR 26347928.

- ^ "Don't blame aging boomers | Toronto Star". Thestar.com. 2011-09-13. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ^ "Don't blame the elderly for health care costs". .canada.com. 2008-01-30. Archived from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ^ "The Silver Tsunami That Isn't". Umanitoba.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-10-02. Retrieved 2013-03-20.

- ^ Bovenberg, Lans; Uhlig, Harald; Bohn, Henning; Weil, Philippe (2006-01-01). "Pension Systems and the Allocation of Macroeconomic Risk [with Comments]". NBER International Seminar on Macroeconomics. 2006 (1): 241–344. doi:10.1086/653983. ISSN 1932-8796.

- ^ Crespo Cuaresma, Jesús; Lutz, Wolfgang; Sanderson, Warren (2013-12-04). "Is the Demographic Dividend an Education Dividend?". Demography. 51 (1): 299–315. doi:10.1007/s13524-013-0245-x. ISSN 0070-3370. PMID 24302530.

- ^ White, Mercedia Stevenson; Burns, Candace; Conlon, Helen Acree (October 2018). "The Impact of an Aging Population in the Workplace". Workplace Health & Safety. 66 (10): 493–498. doi:10.1177/2165079917752191. ISSN 2165-0799. PMID 29506442. S2CID 3664469.

- ^ World Health Organization. "Global age-friendly cities: a guide" (PDF). WHO. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Daly, M; Lewis, J (2000). "The concept of social care and the analysis of contemporary welfare states". British Journal of Sociology. 51 (2): 281–298. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2000.00281.x. PMID 10905001.

- ^ Mohan, J (2003). "Geography and social policy : spatial divisions of welfare". Progress in Human Geography. 27 (3): 363–374. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.456.615. doi:10.1191/0309132503ph432pr. S2CID 54724709.

- ^ Trydegard, G-B; Thorslund, M (2001). "Inequality in the welfare state ? Local variation in care of elderly – the case of Sweden". International Journal of Social Welfare. 10 (3): 174–184. doi:10.1111/1468-2397.00170.

- ^ Rosenberg, M W (1999). "Vieillir au Canada : les collectivités riches et les collectivités pauvres en services". Horizons. 2: 18.

- ^ Aronson, J; Neysmith, S M (2001). "Manufacturing social exclusion in the home care market". Canadian Public Policy. 27 (2): 151–165. doi:10.2307/3552194. JSTOR 3552194.

- ^ Sánchez-González, Diego; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Vicente (2016). Environmental Gerontology in Europe and Latin America. New York: Springer Publishing Company. p. 284. ISBN 978-3-319-21418-4.

- ^ Rowles, Graham D.; Bernard, Miriam (2013). Environmental Gerontology: Making Meaningful Places in Old Age. New York: Springer Publishing Company. p. 320. ISBN 978-0826108135.

- ^ Scheidt, Rick J.; Schwarz, Benyamin (2013). Environmental Gerontology. What Now?. New York: Routledge. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-415-62616-3.

- ^ Sanchez-Gonzalez, D (2015). "The physical-social environment and aging from environmental gerontology and geography. Socio-spatial implications for Latin America". Revista de Geografía Norte Grande. 60 (1): 97–114. doi:10.4067/S0718-34022015000100006.

- ^ Uhlenberg, P (1992-01-01). "Population Aging and Social Policy". Annual Review of Sociology. 18 (1): 449–474. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.18.1.449. ISSN 0360-0572. PMID 12343802.

- ^ a b Ogonda, Job (May 2006). "Age Discrimination in Africa" (PDF).

- ^ Rowland, D. T. (2012). Population aging: the transformation of societies. International perspectives on aging. Dordrecht ; New York: Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-4049-5.

- ^ Gerlock, Edward (May 2006). "Discrimination of Older People in Asia" (PDF).

- ^ Getzen, T. E. (1992-05-01). "Population Aging and the Growth of Health Expenditures". Journal of Gerontology. 47 (3): S98–S104. doi:10.1093/geronj/47.3.s98. ISSN 0022-1422. PMID 1573213.

Additional references

- Gavrilov L.A., Heuveline P. Aging of Population. In: Paul Demeny and Geoffrey McNicoll (Eds.) The Encyclopedia of population. New York, Macmillan Reference USA, 2003, vol.1, 32–37.

- United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2004 Revision Population Database, Population Division, 2004.

- Gavrilova N.S., Gavrilov L.A. Aging Populations: Russia/Eastern Europe. In: P. Uhlenberg (Editor), International Handbook of the Demography of Aging, New York: Springer-Verlag, 2009, pp. 113–131.

- Jackson R., Howe N. The Greying of the Great Powers, Washington: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2008 Major Findings Archived 2009-04-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Goldstone, J. A., Grinin, L., and; Korotayev, A. Research into Global Ageing and its Consequences / History & Mathematics: Political Demography & Global Ageing. Volgograd, Uchitel Publishing House, 2016.

External links

- HelpAge International and UNFPA: Ageing in the 21st Century - A Celebration and A Challenge report (2012)

- Global AgeWatch - website providing latest data, trends and response to global population ageing

- AARP International: The Journal - a quarterly international policy publication on global aging (2010)

- Deloitte study (2007) - Serving the Aging Citizen Archived 2008-10-13 at the Wayback Machine

- CoViVE Consortium Population Ageing in Flanders and Europe

- UN Programme on Ageing

- Oxford Institute of Population Ageing Archived 2021-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Human Development Trends 2005 Presentation on UN Human Development Report 2005 Archived 2008-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- David N. Weil (2006). "Population Aging" (PDF). (59.8 KB)

- Jill Curnow. 2000. Myths and the fear of an ageing population Archived 2008-10-31 at the Wayback Machine (65.6 KB)

- Judith Healy (2004). "The benefit of an ageing population" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-15. Retrieved 2006-11-06. (215 KB)

- Aging Population and Its Potential Impacts Archived 2016-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Population Aging and Public Infrastructure in Developed Countries

- Projections of the Senior Population in the United States

- Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research website