Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

| Globe rupture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Open globe, globe laceration, globe penetration, globe perforation |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Open-globe injuries (also called globe rupture, globe laceration, globe penetration, or globe perforation) are full-thickness eye-wall wounds requiring urgent diagnosis and treatment.[1]

Classification

In 1996 Kuhn et al. created the Birmingham eye trauma terminology (BETT) to standardize the language used to describe traumatic ocular injuries internationally.[2] The BETT schema classifies open globe injuries as a laceration or a rupture. A ruptured globe occurs when rapid intraocular pressure elevation secondary to blunt trauma results in eyewall failure.[3] The rupture site may be at the point of impact but more commonly occurs at the weakest and thinnest areas of the sclera.[4] Regions prone to rupture are the rectus muscle insertion points, optic nerve insertion point, limbus, and prior surgical sites.[1][4] Globe lacerations occur when a sharp object or projectile contacts the eye causing a full-thickness wound at the point of contact. Globe lacerations are further sub-classified into penetrating or perforating injuries.[3] Penetrating injuries result in a single, full-thickness entry wound. In contrast, perforating injuries produce two full-thickness wounds at the entry and exit sites of the projectile.[3] A penetrating globe injury with a retained foreign object, called an intraocular foreign body, has a different prognosis than a simple penetrating trauma. Therefore, intraocular foreign body injuries are considered a distinct type of ocular injury.[4]

Open-globe injuries are also classified by the anatomic region or zone of injury:

- Zone 1- injury involves the cornea and limbus.

- Zone 2- injury involves the anterior 5mm of the sclera.

- Zone 3- injury involves the sclera, more than 5mm posterior to the limbus.[3]

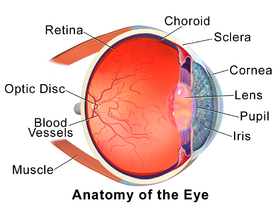

Anatomy

The eye wall is composed of three layers that lie flat against each other to form the eyeball. The external layer is a tough, white membrane called the sclera with a clear dome at the front of the eye called the cornea. The line where the sclera and cornea converge is known as the limbus.[5] The middle layer consists of the colored part of the eye known as the iris, a muscular structure behind the iris responsible for focusing the lens known as the ciliary body, and a layer of blood vessels known as the choroid. The retina is the innermost layer of the eye. The retina contains nerve cells responsible for sensing light and sending visual information to the brain.[6]

The eye can also be divided into three chambers:

- Anterior chamber: (between the cornea and iris)

- Posterior chamber: (between the iris and lens)

- Vitreous chamber: (between the lens and retina)[7]

Epidemiology

There are an estimated 3.5 eye injuries per 100,000 people annually worldwide.[5] The most frequently reported mechanism of injury was trauma by foreign objects (metal, sand, wood), shotgun injuries, motor vehicle accidents, and falls in the home. All mechanisms of injury were more prevalent in males except domestic falls, where a majority of patients were female.[8] Males comprise 80% of open globe injuries, with men between 10 and 30 years of age at the most significant risk.[5]

The mechanism and classification of open-globe injury may also vary by age. Penetrating eye lacerations due to pellet-gun, sport, motor vehicle, or fight-related injuries are more common in adolescent males. Whereas young men tend to sustain penetrating or perforating eye injuries at work, during an assault, or due to alcohol and drug-related accidents. Globe rupture is more common than eyewall lacerations in older patients, with ground-level falls the most common mechanism in those over 75 years of age.[5]

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms of an open-globe injury include eye pain, foreign body sensation, eye redness, and blurry or double vision.[9] While globe injuries are commonly associated with peri-ocular trauma that may obstruct diagnosis,[4] several signs suggest open-globe damage:

- Visible corneal or scleral laceration

- Sub-conjunctival hemorrhage

- Protruding foreign bodies

- Vitreous fluid leakage

- Changes in iris or pupil shape[5]

Diagnosis

Life-threatening-injuries should be evaluated first in those with eye injuries, with life-saving treatments provided before an eye examination.[3] When examining a known or suspected open-globe injury, it is vital to avoid applying pressure to the eye. A sudden increase in intraocular pressure could cause the extrusion of ocular contents.[4] Therefore, the initial assessment does not involve tonometry or eversion of eyelids.[1]

Examination

A Snellen chart or near card may be used to test visual acuity. If visual impairment is significant, evaluation can be done by evaluating the ability to count fingers, see hand movement, or perceive light.[1] Visual acuity assessment might not be possible due to age and developmental capability in children or preexisting visual impairment in older patients.[5]

A slit lamp exam allows a detailed inspection of the conjunctiva and sclera and improves the detection of globe injury. Slit lamp exam findings like decreased anterior chamber depth or damage to posterior chamber structures indicate open-globe injury.[3]

A seidel test detects more subtle or partially self-sealing open-globe injuries. Fluorescein dye is applied to the eye's surface to detect leakage of clear fluid originating from the wound using a Wood's lamp or blue light.[4] This test is avoided in obvious globe injury.[1]

Imaging

Non-contrast maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) is the imaging modality recommended for ocular trauma. However, CT scan findings should are not the sole determining factor for identifying open-globe injuries. CT scans have a 50 – 80% sensitivity and 90 - 100% specificity for open-globe injuries.[4] CT scan findings to suggest open globe injury include:

- Altered globe contour

- Decreased anterior chamber depth

- Globe volume loss

- Presence of an intraocular foreign body

- Intraocular air[4]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is avoided during the initial evaluation, particularly if metallic foreign bodies are suspected.[1] Ultrasound can detect intraocular foreign bodies and evaluate posterior chamber structures. However, direct pressure on the globe during an ultrasound can worsen the injury.[3]

Treatment

Open-globe injuries require urgent evaluation by an ophthalmologist. Initial treatment includes bed rest with a 30-degree elevation of the head, proactive management of pain and nausea, and placement of an eye shield. These measures prevent further damage and limit increases in intraocular pressure.[1][4]

Endophthalmitis or internal eye infection occurs at a rate as high as 30% especially in cases complicated by an intraocular foreign body.[10] Management with 48 hours of intravenous antibiotics decreases the rate of post-traumatic endophthalmitis and its potentially devastating consequences.[10] Vancomycin plus ceftazidime cover infections caused by common organisms (e.g. Bacillus species, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Streptococcal species, and gram-negative organisms).[4][11] Tetanus prophylaxis may be considered, depending on the type of injury and the time since the last immunization.[4]

Surgical repair of an open-globe injury within 24 hours of injury is ideal.[4] After surgical repair, patients should avoid strenuous activities like heavy lifting and exercise and wear an eye shield or other protective eyewear.[3]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Blair, Kyle; Alhadi, Sameir A.; Czyz, Craig N. (2022), "Globe Rupture", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31869101, retrieved 2022-10-14

- ^ Justin, Grant A. (2022-06-07). "Birmingham Eye Trauma Terminology (BETT) - EyeWiki". eyewiki.aao.org. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wang, Daniel; Deobhakta, Avnish (2020-08-01). "Open Globe Injury: Assessment and Preoperative Management". American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Zhou, Yujia; DiSclafani, Mark; Jeang, Lauren; Shah, Ankit A (2022-08-10). "Open Globe Injuries: Review of Evaluation, Management, and Surgical Pearls". Clinical Ophthalmology. 16: 2545–2559. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S372011. ISSN 1177-5467. PMC 9379121. PMID 35983163.

- ^ a b c d e f Andreoli, Christopher M.; Gardiner, Matthew F. (2022-02-15). "Open globe injuries: Emergency evaluation and initial management". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2022-10-14. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ "Anatomy of the Eye | Kellogg Eye Center | Michigan Medicine". www.umkelloggeye.org. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ Kolb, Helga (1995), Kolb, Helga; Fernandez, Eduardo; Nelson, Ralph (eds.), "Gross Anatomy of the Eye", Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System, Salt Lake City (UT): University of Utah Health Sciences Center, PMID 21413392, retrieved 2022-10-14

- ^ Kousiouris, Panagiotis; Klavdianou, Olga; Douglas, Konstantinos A A; Gouliopoulos, Nikolaos; Chatzistefanou, Klio; Kantzanou, Maria; Dimtsas, Georgios S; Moschos, Marilita M (2022-01-05). "Role of Socioeconomic Status (SES) in Globe Injuries: A Review". Clinical Ophthalmology. 16: 25–31. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S317017. ISSN 1177-5467. PMC 8749045. PMID 35027817.

- ^ Patel, Sayjal J.; Lim, Jennifer I.; Hsu, Jason; Parker, Paul R.; Murchison, Anna; Shah, Vinay A.; Feldman, Brad H. (2022-08-04). "Ocular Penetrating and Perforating Injuries - EyeWiki". eyewiki.aao.org. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ a b Relhan, Nidhi; Forster, Richard K.; Flynn, Harry W. (2018). "Endophthalmitis: Then and Now". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 187: xx–xxvii. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.11.021. ISSN 0002-9394. PMC 5873969. PMID 29217351.

- ^ Jindal, Animesh; Pathengay, Avinash; Mithal, Kopal; Jalali, Subhadra; Mathai, Annie; Pappuru, Rajeev Reddy; Narayanan, Raja; Chhablani, Jay; Motukupally, Swapna R; Sharma, Savitri; Das, Taraprasad; Flynn, Harry W (2014-02-18). "Endophthalmitis after open globe injuries: changes in microbiological spectrum and isolate susceptibility patterns over 14 years". Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection. 4 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1869-5760-4-5. ISSN 1869-5760. PMC 3932506. PMID 24548669.