Infrastructure tools to support an effective radiation oncology learning health system

Contents

| |||

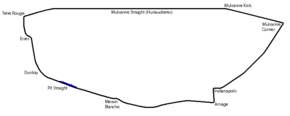

The 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 34th Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 18 and 19 June 1966.[1][2] It was also the seventh round of the 1966 World Sportscar Championship season. This was the first overall win at Le Mans for the Ford GT40 as well as the first win for an American constructor in a major European race since Jimmy Murphy's triumph with Duesenberg at the 1921 French Grand Prix.[3] It was also the debut Le Mans start for two significant drivers: Henri Pescarolo, who went on to set the record for the most starts at Le Mans; and Jacky Ickx, whose record of six Le Mans victories stood until beaten by Tom Kristensen in 2005.

Regulations

The year 1966 saw the advent of a completely new set of regulations from the CSI (Commission Sportive Internationale – the FIA's regulations body) – the FIA Appendix J, redefining the categories of motorsport in a numerical list. GT cars were now Group 3 and Prototypes were now Group 6, Sports Cars were still Group 4 and Special Touring Cars was a new category defined by Group 5.[4] (Group 1 and 2 covered other Touring Cars, Group 7 led to the Can-Am series, with Group 8 and 9 for single-seaters).[5]

As Group 7 were ineligible for FIA championship events, the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) opened its entry list to Group 3, 4 and 6. The FIA mandated minimum annual production runs of 500 cars for Group 3 (up from 100 previously[6][7]) and 50 for Group 4,[7] which also had a maximum engine capacity of 5000cc. There were no engine limits on the GTs or Prototypes. As before, the Groups were split up in classes based on engine size, there was a sliding scale of a minimum weight based on the increasing engine size (from 450 to 1000 kg for 500 to 7000cc) as was fuel-tank capacity (60 to 160 litres).[5]

Along with the new Appendix J, after four years of focus on GT racing the FIA announced the International Manufacturer's Championship, for Group 6 Prototypes (2L / >2L), and the International Sports Car Championship for Group 4 (1.3L / 2L / 5L).[5]

Entries

With the new regulations this year the ACO received a huge 103 entry requests. Such was the interest in Group 6 there were 43 prototypes on the starting grid and only 3 GT cars:

| Category | Classes | Prototype Group 6 |

Sports Group 4 |

GT Group 3 |

Total entries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-engines | 2.0 - 7.0L | 21 | 5 (+3 reserve) | 1 (+1 reserve) | 27 (+4 reserves) |

| Medium-engines | 1.6 - 2.0L | 12 | 1 (+1 reserve) | 2 | 15 (+1 reserve) |

| Small-engines | 1.0 - 1.3L | 13 (+2 reserves) | 0 | 0 | 13 (+2 reserves) |

| Total Cars | 46 (+2 reserves) | 6 (+4 reserves) | 3 (+1 reserve) | 55 (+7 reserves) |

After 2 years of its 3-year program, Ford had very little to show for its immense investment. Extensive work was done in the wind tunnel, and improving the brakes, handling and engine – not least improving the fuel economy.[8][9][10][11] The 7-litre Ford NASCAR race engine now put out ca. 550 bhp but was registered as "485 hp" as a result of Ford's lowered rev-limit setting for the 24h race.[7] The new year started with promise with Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby winning both the inaugural 24 Hours of Daytona and then 12 Hours of Sebring.[9] Copying Ferrari's tactic of overwhelming numbers, they put in fifteen Mark II entries; eight were accepted by the ACO. This time six were built and prepared by Holman & Moody. Shelby ran three cars for Americans Dan Gurney and Jerry Grant, Miles was now paired with New Zealander Denny Hulme after Ruby had been injured in a plane crash a month earlier.[12] The third car was the all-Kiwi pairing of Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon. Holman & Moody, the successful Ford NASCAR race team also brought another trio of GT40s as backups, – for Mark Donohue/Paul Hawkins, Ronnie Bucknum/Dick Hutcherson, and Lucien Bianchi/Mario Andretti.[13] One of the big improvements Holman & Moody brought with them was a quick-change brake pad system to save time in the pits.[14]

The British team Alan Mann Racing had two cars prepared by Ford Advanced Vehicles, for Graham Hill/Dick Thompson and John Whitmore/Frank Gardner. Each of the eight cars was painted in a colour from the Mustang road-car range.[15][16]

Ferrari's response to the Mk II was the new Ferrari 330 P3. Shorter and wider than the P2, it kept the same 4-litre engine but with fuel-injection now put out 420 bhp.[11] The works team had a pair of closed-cockpit versions for John Surtees/Ludovico Scarfiotti and former winners Lorenzo Bandini/Jean Guichet. An open-cockpit variant was given to the North American Racing Team (NART) for Pedro Rodriguez/Richie Ginther. But their race preparation had been limited by strike action in Italy.[17][9][18]

NART also entered a long-tailed P2, rebodied by Piero Drogo and driven by last year's winner Masten Gregory with Bob Bondurant. There were also P2/P3 hybrids for the Ecurie Francorchamps (Dumay/"Beurlys") and Scuderia Filipinetti (Mairesse/Müller). Finally there was a P2 Spyder for Maranello Concessionaires (Attwood/Piper).[17][19] Fighting on two fronts, the company also took on Porsche in the 2-litre class with its Dino 206 S with a pair from NART and another for Maranello. Nino Vaccarella, race winner in 1964, was furious when he found out he was ‘demoted’ to drive the Dino rather than the P3 and threatened to walk out, but did, in the end run the car.[20][21]

Chevrolet was the other player in the over 2-litre class. Ex-Ferrari engineer Giotto Bizzarrini had fallen out with Renzo Rivolta and with his own company brought his new design, the P538, but still using the 5.3L Chevrolet engine. The other Chevy was in Texan Jim Hall's Chaparral 2D. The 5.3L small block put out 420 bhp and had a semi-automatic transmission.[18][7] Driven by Phil Hill and Jo Bonnier, they made a big impact winning the Nürburgring round just two weeks earlier.[22]

Porsche came with a new model – the 906 designed by the team led by Ferdinand Piëch. With the 2.0L flat-6 engine from the 911, it had recently been homologated for Group 4 with the requisite 50 cars.[23] It was race-proven too, after winning the Targa Florio the month before. However three "langheck" (long-tail) prototypes were also entered by the works team, driven by Hans Herrmann/Herbert Linge, Jo Siffert/Colin Davis and Udo Schütz/Peter de Klerk.[24]

Alfa Romeo, and its works team Autodelta, had withdrawn from racing for a year to prepare a new car for 1967.[8] But this year, a significant new manufacturer entered the fray: Matra had bought out Automobiles René Bonnet in 1964, rebadging the Djet. However it was a new design that was entered. The M620 had a 2-litre version of the BRM Formula 1 engine developing 245 bhp that could match the Porsches in speed, making 275 kp/h (170 mph). The three cars were driven by up and coming young French single-seater drivers Jean-Pierre Beltoise/Johnny Servoz-Gavin, Jean-Pierre Jaussaud/Henri Pescarolo and Jo Schlesser with Welshman Alan Rees.[25]

Remarkably, given British dominance of the race barely a decade earlier, there were only three British cars in this year's race. Defending class-champions Austin-Healey had two works entries. The other was a Marcos Engineering kit-car based on a Mini Cooper 'S' chassis. Entered by Frenchman Hubert Giraud and driven by Jean-Louis Marnat and Claude Ballot-Lena, the team was able to get a works engine and gearbox from BMC. The spectators laughed at the small car and its apparent resemblance to a flea.[26] But the Mini Marcos would become the 'darling of the crowds' later on in the race.

Alpine, after its poor showing in the previous year, returned with 6 cars. The new A210 had a 1.3L Gordini-Renault engine with a Porsche gearbox making it more durable if only a little faster at 245 kp/h (150 mph). This year a new customer team, the Ecurie Savin-Calberson was supported by Alpine, with former Index winner Roger Delageneste.[27]

Charles Deutsch (CD) brought his new aerodynamic SP66. The car was powered by a 1130cc Peugeot engine, marking the return of the French company last seen in the 1938 race.[28] Another competitor in the small prototypes was ASA. Originally a Ferrari design by Carlo Chiti and Giotto Bizzarrini before their famous walk-out from Ferrari, it was sold to the new Italian company and uprated with a 1290cc engine giving 125 bhp. Two cars were entered, one by ASA and one by NART.[29]

The new Group 4 category started attracting interest as the earlier prototypes were meeting the homologation and production requirements. There were six GT40s entered by customer teams, with the 4.7L engine. Jochen Rindt, the previous year's winner, had moved across from Ferrari to Ford, in the new Canadian Comstock Racing Team. They joined Ford France, Scuderia Filipinetti and new privateers Scuderia Bear and Essex Wire. Joining Skip Scott, team owner of the Essex Wire team, was a 21-year old Jacky Ickx in his Le Mans debut.[30][31]

Up against them was Ed Hugus’ modified Ferrari 275 GTB and the Equipe Nationale Belge ran its 250 LM. Porsche also ran three regular 906s in the Sports category, two works entries as well as one for their Paris importer Toto Veuillet.

With Shelby now fully concentrated on the Ford program, the Cobra GTs were abandoned. There were only three GT entries: the Ferrari customer teams Ecurie Francorchamps and Maranello Concessionaires both entered a 275 GTB. The third was a quiet though significant entry: Jacques Dewes, ever the pioneering privateer, brought the first Porsche 911 to Le Mans. Production of what would become the ubiquitous Le Mans car had started in late 1964 and the new 911 S model had its ‘boxer’ 6-cylinder engine tuned to 160 bhp.[32]

Finally, in a sub competition of its own, there was the tire race between Firestone, Dunlop, and Goodyear.[8]

Practice

Once again there was rain at the April testing weekend. And once again there was tragedy with a fatal accident. American Walt Hansgen's Ford hit water on the pit straight and aquaplaned. He aimed for the escape road at the end of the straight, not realising it was blocked by a sandbank, which he hit at about 190 km/h (120 mph). Taken with critical injuries to the American military hospital at Orléans, he died five days later.[15][12][21]

A notable absentee at the test weekend was the Ferrari works team.[8][21] Chris Amon was fastest at the test weekend in the experimental Ford J-car with a 3:34.4 lap.[7] But come race-week it was Gurney who put in the fastest qualifying lap of 3:30.6, a second faster than his stablemates Miles, Gardner and McLaren. Ginther was 5th in the fastest Ferrari with a 3:33.0, with Parkes and Bandini in 7th and 8th respectively. Phil Hill, in the Chaparral, broke up the Ford-Ferrari procession in 10th.[33]

Jo Siffert put the quickest Porsche 22nd on the grid with 3:51.0, with Nino Vaccarella's Ferrari in 24th (3:53.5) and Jo Schlesser's Matra just behind it (3:53.5). Over the test weekend, Mauro Bianchi had surprised many in the 1-litre Alpine, going as fast as the 1959 Ferrari Testa Rossas.[27][21] The quickest Alpine in practice was Toivonen/Jansson (4:20.1), well ahead of the best CD (Ogier/Laurent 4:27.5) and the Austin-Healey's (4:45.1) and ASAs (4:49.8).[33]

There were also two significant dramas in practice. The biggest news was the walkout of Ferrari's lead driver John Surtees. He and team manager Eugenio Dragoni had decided that he, as the fastest Ferrari driver and driving with Mike Parkes, would act as the hare to bait and break the Fords. He was also still recovering from a big accident the previous year and would hand over to Scarfiotti if he got overly tired. Yet during raceweek, with news that new FIAT chairman Gianni Agnelli would be at the race, Dragoni changed the plan, putting Scarfiotti (Agnelli's nephew) in first. Surtees was furious and stormed off to Maranello to argue his case with Enzo Ferrari.[21] Not listened to, Surtees, Ferrari's 1964 F1 World Champion, quit the team.[17][19][20]

The second incident was more serious – Dick Thompson in the Alan Mann Ford Mk II collided with Dick Holqvist who was going far slower in the Scuderia Bear Ford GT40 and pulled right in front of him at Maison Blanche.[19] Holqvist spun off with heavy damage, while Thompson was able to get back to the pits. While repairing the damage, officials told the team that they were disqualified for Thompson leaving the scene of a major accident. Thompson was adamant he had advised pit officials, and in the hearing Ford's director of racing Leo Beebe threatened to withdraw all Fords. He was supported by Huschke von Hanstein who was prepared to withdraw the Porsche team as well.[21] In the end, the car was reinstated though Thompson was banned. This still posed a problem for Ford as they were lacking spare drivers, with injuries with A. J. Foyt, Jackie Stewart and Lloyd Ruby.[19] In the end Australian Brian Muir, who was in England was flown over to France. He did his two laps, his first ever at Le Mans on raceday morning to qualify.[30][16][20]

Race

Start

On a cool and cloudy afternoon, it was Henry Ford II this year who was the honorary starter.[21] Last-minute raindrops caused a flurry of tyre changes and some cars switched from Firestone to Goodyear or Dunlop.[16][20] At the end of the first lap Ford's cars led – Hill ahead of Gurney then Bucknum, Parkes in the Ferrari, followed by Whitmore's Ford, the Chaparral, then the GT40s of Scott and Rindt.[16] There had been instant excitement when Edgar Berney spun his Bizzarrini on the start-line amongst the crowd of departing cars.[34][35][21] Miles had to pit after the first lap to fix his door because earlier, he had slammed the door on his helmet. Also pitting on the first lap was Paul Hawkins whose Ford broke a halfshaft going down the Mulsanne Straight lurching him sideways at nearly 350 km/h.[16] The Holman & Moody crew took 70 minutes to repair it only for Mark Donohue to have the rear boot blow off down the Mulsanne and find the differential had been terminally damaged.[15][16][36]

On the third lap Gurney took the lead, which he held onto until the first pit-stops. McLaren was being delayed by his tyres going off, so the team quietly changed from Firestones to Goodyears.[15] After only 9 laps, Rindt's Ford blew its engine at the end of the Mulsanne straight, so there would be no consecutive win.[30] At the end of the first hour Fords were 1-2-3, with Gurney leading by 24 seconds from Graham Hill and Bucknum. Fourth, 20 seconds further back, was the first NART Ferrari, of Rodriguez. Meanwhile, Miles had been putting in extremely fast laps, breaking the lap record and getting back up to 5th place. Parkes was 6th ahead of Bonnier in the Chaparral who had already been lapped. Within another hour Miles and Hulme had taken the lead.[37][9]

At 8pm, only the Miles and Gurney Fords and Rodriguez's Ferrari were on the lead lap (#64).[38] At dusk it started to drizzle, reducing the power advantage of the big Fords, and allowing the Ferraris to keep in touch. The Fords were further delayed as a number chose to change brake pads early.[37] By then all three Dinos were out with mechanical issues, removing one threat to Porsche.[21] A major accident occurred when Jean-Claude Ogier's CD got loose on spilt oil at the Mulsanne kink and was hit hard side-on by François Pasquier in the NART ASA. Both cars hit the wall and caught fire, and Ogier was taken to the hospital with two broken arms.[29][28][39]

Night

After 6 hours, heavy rain was pouring down. Ginther's NART Ferrari was leading from Parkes, chased by the Fords of Miles and Gurney on the same lap, McLaren a lap behind, then Bandini and Andretti two laps back. But Andretti was soon sidelined with a blown headgasket, as was the Hill/Muir Ford which had broken its front suspension coming out of Arnage corner.[15][40] As the rain eased, the Fords of Miles and Gurney retook the lead. Just before midnight Robert Buchet aquaplaned coming over the crest at the Dunlop Bridge and crashed the French Porsche.[24] The Chaparral had been running well initially, getting as high as 5th, until a broken alternator stopped them also just before midnight while running in 8th.[22]

Another heavy downpour at 12.30 contributed to a big accident in the Esses. Guichet had just spun his Ferrari in the rain and got away when Buchet arrived and crashed his Porsche. Then Schlesser's Matra ran into the CD of Georges Heligouin avoiding the accident. As the damage was being cleared, Scarfiotti crashed his P3 into the Matra and all four cars were wrecked, although only Scarfiotti was taken to hospital, with minor bruising.[37][39]

During the night the Ferraris started to suffer from overheating. When the NART P3 retired from 4th with a broken gearbox at 3am, and the Filipinetti car of Mairesse/Müller from 5th an hour later, the Ferrari challenge was spent – there would be no privateer-saviours for the marque this year. At halfway the Ford Mk IIs held the top-4 places (Miles/Hulme, Gurney/Grant, McLaren/Amon, Bucknum/Hutcherson) with GT40s in 5-6-8: Essex, Filipinetti and Ford-France (Revson/Scott, Spoerry/Sutcliffe, Ligier/Grossman). Siffert/Davis were leading a train of Porsches in 7th and the nearest Ferrari was the Bandini/Guichet P3 limping in 12th. Ford told their cars to drop to 4-minute laps, but Gurney and Miles kept racing hard for the lead.[40]

Morning

What could have been a procession was anything but for Ford. At 8 am, a pit-stop for the Filipinetti Ford running 5th spilled petrol on a rear tyre. On his out-lap Spoerry lost traction and spun at the Esses wrecking the car. The Ford-France and Essex cars had already retired with engine issues during the night.[30]

At 9am the Gurney/Grant car, which had been dicing for the lead with Miles & Hulme (against strict team orders), retired from 1st when the car blew a headgasket. That left Ford with only three Mk IIs left (albeit running 1-2-3) as all the GT40s had retired as well. Porsches now held the next five places and the two Ferrari GTs were 9th and 10th chased by the Alpines.

Finish and post-race

With the field covered it was now that Leo Beebe, Ford racing director, contrived to stage a dead heat by having his two lead cars cross the line simultaneously.[41] The ACO told him this would not be possible — given the staggered starting formation, the #2 car would have covered 20 metres further, and thus be the race winner. But Beebe pushed on with his plan anyway.[37][42]

At the last pit stop, the Mark IIs were still in front. Miles/Hulme were leading, followed by McLaren/Amon holding station on the same lap. The gold Bucknum/Hutcherson car was third, but twelve laps behind. Miles was told to ease off to allow McLaren to catch up with him. Just before 4pm, it started to drizzle again. As the Miles's #1 car and McLaren's #2 car approached the finish, McLaren crossed the finish line just ahead of Miles. Miles, who was upset about the team orders, lifted off to allow McLaren to finish a length ahead.[15][42][43][44][45] Additionally, McLaren had covered more distance during the race due to the starting positions. Regardless of the reason, McLaren's #2 was declared the winner.[46]

At their last pitstop, the 7th-placed Porsche of Peter Gregg and Sten Axelsson was stopped by engine problems. Gregg parked the car waiting for the last lap, but at 3.50pm he could not get it restarted and missed the formation finish. The other Porsches came in 4th to 7th led by Siffert/Davis, who also claimed the Index of Performance. The Stommelen/Klass car in 7th was the first, and only, Sports car to finish. Finally, the new 911 GT ran well and finished 14th starting a long record of success.[24]

Four Alpines finished this year, 9-11-12-13, with that of Delageneste/Cheinisse from the Ecurie Savin-Calberson winning the Thermal Efficiency Index.[27] The final finisher was the little Mini Marcos. Formerly the object of laughter, it had become a crowd favourite running like clockwork. As car after car ran into trouble and dropped out, the little Marcos, by this time nicknamed 'la puce bleue' (the blue flea) wailed on. Despite finishing 26 laps behind the rest of the field.[26][7] the car eventually came home at an incredible 15th overall.

It had taken three attempts for Ford to win Indianapolis and the NASCAR Championship, and now it added the Le Mans 24 Hours. Chrysler had first entered in 1925, and after 41 years it was the first win for an American car.[31] The official Ford press release, dated July 5, 1966, claimed:

The McLaren-Amon and the Miles-Hulme cars were running within seconds of each other as the race neared its end, with the Bucknum-Hutcherson car hanging back as insurance. A decision was made in the Ford pits to have the cars finish side by side in what hopefully would be considered a dead heat. All three cars went over the finish in formation, but any chance for a dead heat disappeared when officials discovered a rule that in case of a tie, the car that had started further down the grid had travelled the farther distance. Since McLaren and Amon had started 60 feet behind Miles and Hulme, they were declared the winners. Both New Zealanders who now reside in England, it was the most important victory yet for the two youngsters. McLaren, who builds his own Formula and sports cars, is 28. Amon 22, is the youngest winner in the history of the event. It was a record shattering performance as the winning car covered more miles (3,009.3) at a faster speed (125.38 mph) than any previous entry. It demonstrated that production engines could compete with racing powerplants and that an American-built car could top Europe's best.[47]

The Ford team's decision was a big disappointment for Ken Miles, who was aiming for the 'Endurance Racing Triple Crown'—winning Daytona-Sebring-Le Mans—as a reward for his investment in the GT40 development. "I'm disappointed, of course, but what are you going to do about it."[48] Beebe also later admitted he had been annoyed with Miles racing Gurney, disregarding team orders by potentially risking the cars' endurance.[15] Two months later, Ken Miles died at Riverside while testing the next generation Ford GT40 J-Car, which became the Mk IV that won Le Mans in 1967.[15][42][49]

In a race of attrition it was fortunate the big teams brought such quantity – only 3 of the 13 Fords finished and only the two GTs finished from the 14 Ferraris entered. By contrast, 5 of the 7 Porsches finished (including their 911 in the GT class) as did four of the six Alpines, showing much better reliability. It was the first time that the 3000 miles/125 mph mark had been exceeded.[31]

With the bitter failure of Ferrari's 330 P3 mirroring the failure of the Ford prototypes the previous year (and with salt rubbed into the wound with Ford's formation finish), the "Ford-Ferrari War" moved into its climactic phase. The Le Mans results boosted Ford over Ferrari for the 1966 Manufacturers' Championship. Ford's answer to Ferrari's next weapon, the 330 P4, was delayed by development problems, handing Ferrari a rematch with the Mk IIs that so dominated them at LeMans, at the 1967 Daytona 24 Hours. After a defective batch of transaxle shafts sank Ford's effort, Ferrari took a 1-2-3 finish with their new P4s and returned the favor of Ford's victory formation. Ford's Mark IV was ready in time for the 12 Hours of Sebring, where it won on its maiden outing. Three more examples were produced and prepared for the Le Mans 24 Hours, while Ford's championship hopes rested on the older GT40s and the new GT40-derived Mirages to gain points in the intervening races. After a disappointing showing at Monza and a controversial denial of championship points from a Mirage win at the Spa event, Ford saw limited opportunity for taking the Manufacturers' title again and instead concentrated on a last hurrah at Le Mans, where the leading Mark IV, driven by Dan Gurney and A. J. Foyt, won handily. Ferrari took the Manufacturers' title for 1967, edging up-and-coming Porsche by two points.

The Ford-Ferrari War was ended by new rules for 1968 that eliminated the P4s and Mark IVs from eligibility for the Sports Prototype class with a 3-litre engine capacity limit. The GT40s met the production requirement and 5 litre limit for homologation in the new Group 4 class. Ferrari found the production requirement for homologating the P4 under Group 4 daunting and withdrew from competition in the sport-racer classes. Neither Ford nor Ferrari fielded a factory team for the Manufacturers' Championship that year; however, the John Wyer team running the Group 4 GT40s brought home the title for Ford and in 1969 achieved wins with the GT40 at Sebring and Le Mans. When Ferrari was able to enter a homologated car for 1970, the class they competed in was dominated by the Porsche 917.

Several cars of the original 24-hours race have survived and have been restored to their former glory. The crowd-pleasing Mini Marcos was club raced, rallied and hill climbed, road registered twice and repainted five times only to be stolen in the night of 30 October 1975 from beneath a flat in Paris. Three days earlier Marcos-boss Harold Dermott had made a deal to buy the car with the intention to restore it and put on museum display. Several people searched for the car ever since, but it was only found back in December 2016 in Portugal by Dutchman Jeroen Booij.[citation needed]

Legacy in popular culture

Go Like Hell

The race became the subject of a 2009 book, detailing the race and the famous background rivalry between Enzo Ferrari and Henry Ford II, by A. J. Baime[50][51] titled Go Like Hell—the words shouted by Bruce McLaren to Chris Amon as they drove to their famous victory.[52]

Rumors of a movie adaptation of the book, an Amazon best seller,[53] circulated from 2013 to 2015.[54][55] The book attained a "4.5 star" rating by book review website GoodReads.com.[56]

The 24 Hour War

A 2016 documentary film, produced and directed by Americans Nate Adams and comedian Adam Carolla, features the Le Mans rivalry between Ferrari and Ford. The production was well received critically, attaining a "100%" rating on review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.[57][58]

Ford v Ferrari

Ford v Ferrari (known as Le Mans '66 in the UK and other territories) is a sports drama film distributed by 20th Century Fox, based on the rivalry between Ford and Ferrari for dominance at Le Mans. Directed by James Mangold, starring Matt Damon and Christian Bale in the roles of Carroll Shelby and Ken Miles, respectively. The film was released on 15 November 2019. At the 92nd Academy Awards, the film received four nominations, including Best Picture and Best Sound Mixing, and won for Best Sound Editing and Best Film Editing.

Official results

Finishers

Results taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO[59] Class Winners are in Bold text.

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P +5.0 |

2 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 360 | ||

| 2 | P +5.0 |

1 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 360 | ||

| 3 | P +5.0 |

5 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 348 | ||

| 4 | P 2.0 |

30 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | Porsche 1991cc F6 | 339 | |

| 5 | P 2.0 |

31 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | Porsche 1991cc F6 | 338 | |

| 6 | P 2.0 |

32 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | Porsche 1991cc F6 | 337 | |

| 7 | S 2.0 |

58 (reserve) |

Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 Carrera 6 | Porsche 1991cc F6 | 330 | |

| 8 | GT 5.0 |

29 | Ferrari 275 GTB Competizione |

Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 313 | ||

| 9 | P 1.3 |

62 (reserve) |

Alpine |

Alpine A210 | Renault-Gordini 1296cc S4 | 311 | |

| 10 | GT 5.0 |

57 (reserve) |

Ferrari 275 GTB Competizione |

Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 310 | ||

| 11 | P 1.3 |

44 | Alpine A210 | Renault-Gordini 1296cc S4 | 307 | ||

| 12 | P 1.3 |

45 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | Renault-Gordini 1296cc S4 | 307 | |

| 13 | P 1.3 |

46 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | Renault-Gordini 1296cc S4 | 306 | |

| 14 | GT 2.0 |

35 | (private entrant) |

Porsche 911S | Porsche 1991cc F6 | 284 | |

| 15 | P 1.3 |

50 | (private entrant) |

Mini Marcos GT 2+2 | BMC 1287cc S4 | 258 |

Did not finish

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNF | S 2.0 |

33 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 Carrera 6 | Porsche 1991cc F6 | 321 | Engine (24hr) | |

| DNF | P +5.0 |

3 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 257 | Radiator (18hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.3 |

49 | Austin-Healey Sprite | BMC 1293cc S4 | 237 | Head gasket (21hr) | ||

| DNF | S 5.0 |

14 | Ford GT40 | Ford 4.7L V8 | 233 | Accident (17hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

21 | Ferrari 330 P3 | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 226 | Engine (17hr) | ||

| DNF | S 5.0 |

26 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 275 GTB Competizione |

Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 218 | Clutch (20hr) | |

| DNF | S 5.0 |

28 | Ferrari 250 LM | Ferrari 3.3L V12 | 218 | Engine (18hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.3 |

47 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | Renault 1296cc S4 | 217 | Gearbox (21hr) | |

| DNF | S 5.0 |

59 (reserve) |

Ford GT40 Mk.I | Ford 4.7L V8 | 212 | Engine (15hr) | ||

| DNF | S 5.0 |

15 | Ford GT40 Mk.I | Ford 4.7L V8 | 205 | Ignition (16hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

19 | Ferrari 365 P2 | Ferrari 4.4L V12 | 166 | Gearbox (12hr) | ||

| DNF | S 5.0 |

60 (reserve) |

Ford GT40 | Ford 4.7L V8 | 154 | Engine (11hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

27 | Ferrari 330 P3 Spyder | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 151 | Gearbox (11hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.3 |

48 | Austin-Healey Sprite Le Mans | BMC 1293cc S4 | 134 | Clutch (16hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

17 | Ferrari 365 P2 | Ferrari 4.4L V12 | 129 | Engine (14hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

20 | Ferrari 330 P3 | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 123 | Accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.15 |

55 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | Renault-Gordini 1005cc S4 | 118 | Water pump (20hr) | |

| DNF | P 2.0 |

41 | Matra MS620 | BRM 1915cc V8 | 112 | Gearbox (13hr) | ||

| DNF | P +5.0 |

9 | Chaparral 2D | Chevrolet 5.4L V8 | 111 | Electrics (8hr) | ||

| DNF | P +5.0 |

7 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 110 | Front suspension (8hr) | ||

| DNF | P 2.0 |

34 | Porsche 906/6 Carrera 6 | Porsche 1991cc F6 | 110 | Accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | P 2.0 |

42 | Matra MS620 | BRM 1915cc V8 | 100 | Accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | P +5.0 |

6 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 97 | Head gasket (8hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.15 |

53 | CD SP66 | Peugeot 1130cc S4 | 91 | Accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

18 | Ferrari 365 P2 | Ferrari 4.4L V12 | 88 | Transmission (9hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.15 |

51 | CD SP66 | Peugeot 1130cc S4 | 54 | Accident (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.3 |

54 | ASA GT RB-613 | ASA 1290cc S4 | 50 | Accident (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

24 | Serenissima Spyder | Serenissima 3.5L V8 | 40 | Gearbox (5hr) | ||

| DSQ | P +5.0 |

11 | Bizzarrini P538 Super America | Chevrolet 5.4L V8 | 39 | Pit violation (5hr) | ||

| DNF | P 2.0 |

43 | Matra MS620 | BRM 1915cc V8 | 38 | Oil pump (8hr) | ||

| DNF | P 5.0 |

16 | Ferrari 365 P2 | Ferrari 4.4L V12 | 33 | Water pump (8hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.3 |

61 (reserve) |

per Azione |

ASA GT RB-613 | ASA 1290cc S4 | 31 | Transmission (8hr) | |

| DNF | P +5.0 |

8 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 31 | Clutch (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.15 |

52 | CD SP66 | Peugeot 1130cc S4 | 19 | Clutch (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P 2.0 |

36 | Dino 206 S | Ferrari 1986cc V6 | 14 | Rear axle (3hr) | ||

| DNF | P +5.0 |

4 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | Ford 7.0L V8 | 12 | Differential (5hr) | ||

| DNF | P 2.0 |

38 | Dino 206 S | Ferrari 1986cc V6 | 9 | Engine (3hr) | ||

| DNF | P +5.0 |

10 | Bizzarrini P538 Sport | Chevrolet 5.4L V8 | 8 | Steering arm (3hr) | ||

| DNF | S 5.0 |

12 | Ford GT40 Mk.I | Ford 4.7L V8 | 8 | Engine (3hr) | ||

| DNF | P 2.0 |

25 | Dino 206 S | Ferrari 1986cc V6 | 7 | Water leak (3hr) |

Did not start

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNS | P 1.15 |

56 | Alpine |

Alpine A110 M64 | Renault-Gordini 1005cc S4 | Did not start | |

| DNS | S 5.0 |

63 (reserve) |

Ford GT40 | Ford 4.7L V8 | practice accident | ||

| DNA | P 5.0 |

22 | Ferrari 330 P3 | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | Did not arrive | ||

| DNA | P 5.0 |

23 | Serenissima Spyder | Serenissima 3.5L V8 | Did not arrive | ||

| DNA | P 2.0 |

37 | Dino 206 S | Ferrari 1986cc V6 | Did not arrive | ||

| DNA | P 2.0 |

39 | (private entrant) |

Dino 206 S | Ferrari 1986cc V6 | Did not arrive | |

| DNA | GT 1.6 |

44 | Alfa Romeo Giulia TZ2 | Alfa Romeo 1570cc S4 | Did not arrive |

Class winners

| Class | Prototype winners |

Class | Sports winners |

Class | GT winners | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototype 5000 |

#2 Ford GT40 Mk.II | Amon / McLaren * | Sports 5000 |

- | Grand Touring 5000 |

no entrants | ||

| Prototype 5000 |

no finishers | Sports 5000 |

no finishers | Grand Touring 5000 |

no entrants | |||

| Prototype 4000 |

no finishers | Sports 4000 |

no finishers | Grand Touring 4000 |

#29 Ferrari 275 GTB Competizione |

Courage / Pike | ||

| Prototype 3000 |

no entrants | Sports 3000 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 3000 |

no entrants | |||

| Prototype 2000 |

#30 Porsche 906/6 LH | Siffert / Davis * | Sports 2000 |

#58 Porsche 906/6 | Stommelen / Klass * | Grand Touring 2000 |

#35 Porsche 911 S | "Franc" / Kerguen |

| Prototype 1600 |

no entrants | Sports 1600 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 1600 |

no entrants | |||

| Prototype 1300 |

#62 Alpine A210 M64 | Grandsire / Cella * | Sports 1300 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 1300 |

no entrants | ||

| Prototype 1150 |

no finishers | Sports 1150 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 1150 |

no entrants | |||

* Note: setting a new Distance Record.

Index of thermal efficiency

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P 1.3 |

44 | Alpine A210 | 1.35 | ||

| 2 | P 1.3 |

46 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | 1.33 | |

| 3= | P 1.3 |

45 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | 1.32 | |

| 3= | P +5.0 |

1 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | 1.32 | ||

| 5 | P 1.3 |

62 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | 1.30 | |

| 6 | P +5.0 |

2 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | 1.24 | ||

| 7 | P +5.0 |

5 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | 1.14 | ||

| 8 | P 2.0 |

30 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | 1.09 | |

| 9 | P 2.0 |

31 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | 1.04 | |

| 10 | P 2.0 |

32 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | 1.03 |

- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings.

Index of performance

Taken from Moity's book.[61]

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P 2.0 |

30 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | 1.263 | |

| 2 | P 2.0 |

31 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | 1.259 | |

| 3 | P 1.3 |

62 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | 1.258 | |

| 4 | P 2.0 |

32 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 LH | 1.256 | |

| 5 | P 1.3 |

45 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | 1.240 | |

| 6 | P 1.3 |

44 | Alpine A210 | 1.239 | ||

| 7 | P 1.3 |

46 | Alpine |

Alpine A210 | 1.235 | |

| 8 | S 2.0 |

58 | Engineering |

Porsche 906/6 Carrera 6 | 1.230 | |

| 9= | P +5.0 |

1 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | 1.204 | ||

| 9= | P +5.0 |

2 | Ford GT40 Mk.II | 1.204 |

- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings. A score of 1.00 means meeting the minimum distance for the car, and a higher score is exceeding the nominal target distance.

Statistics

Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO

- Fastest Lap in practice – D.Gurney, #3 Ford GT40 Mk II – 3:30.6secs; 230.10 km/h (142.98 mph)

- Fastest Lap – D.Gurney, #3 Ford GT40 Mk II – 3:30.6secs; 230.10 km/h (142.98 mph)

- Distance – 4,843.09 km (3,009.36 mi)

- Winner's Average Speed – 201.80 km/h (125.39 mph)

- Attendance – 350 000[62]

Challenge Mondial de Vitesse et Endurance standings

As calculated after Le Mans, Round 4 of 4[63]

| Pos | Manufacturer | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | |

| 2 | 18 | |

| 3 | 14 | |

| 4 | 9 | |

| 5 | 3 | |

| 6 | 1 |

- Citations

- ^ Motor Sport, July 1966, Pages 596-597.

- ^ "1966 24 Hours of Le Mans Entry list" – via Sportscars.tv.

- ^ "The ACO statistics of winners" (PDF).

- ^ FIA Annex J 1966, historicdb.fia.com, as archived at web.archive.org

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.208

- ^ Clausager 1982, p.140

- ^ a b c d e f Moity 1974, p.102-4

- ^ a b c d Clarke 1997, p.6-7: Autosport Jun17 1966

- ^ a b c d Fox 1973, p.201

- ^ Clarke 1997, p.18: Road & Track Oct 1966

- ^ a b Armstrong 1966, p.209

- ^ a b Fox 1973, p.198

- ^ Clarke 1997, p.15: Road & Track Oct 1966

- ^ Clarke 1997, p.21: Road & Track Oct 1966

- ^ a b c d e f g h Spurring 2010, p.210-3

- ^ a b c d e f Clarke 1997, p.10: Road & Track Sept 1966

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.217-9

- ^ a b Laban 2001, p.150-1

- ^ a b c d Clarke 1997, p.9: Road & Track Sept 1966

- ^ a b c d Clarke 1997, p.24: Motor Jun25 1966

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Armstrong 1966, p.235

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.227

- ^ Armstrong 1966, p.210

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.220-1

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.222

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.233

- ^ a b c Spurring 2010, p.224

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.231

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.228

- ^ a b c d Spurring 2010, p.214-5

- ^ a b c Clausager 1982, p.147

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.223

- ^ a b Spurring 2010, p.235

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.232

- ^ Clausager 1982, p.144

- ^ Clarke 1997, p.25: Motor Jun25 1966

- ^ a b c d Spurring 2010, p.208-9

- ^ Clarke 1997, p.26: Motor Jun25 1966

- ^ a b Clarke 1997, p.11: Road & Track Sept 1966

- ^ a b Clarke 1997, p.12: Road & Track Sept 1966

- ^ "A look back at the 1966 Le Mans 24 Hours". 5 May 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Fox 1973, p.202

- ^ Clarke 1997, p.13: Road & Track Sept 1966

- ^ "Watch the story of the controversy behind the Ford GT40's photo finish at Le Mans in 1966". Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ "Le Mans 1966: The Golden Mystery – dailysportscar.com". www.dailysportscar.com. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ 1966 Le Mans 24 Hours race report: Ford takes first win Motor Sport Magazine

- ^ "For Immediate Release" (PDF). Ford Division News Bureau. 1966. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ "20 Jun 1966, Page 11 - The Cumberland News at Newspapers.com". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ "Ken Miles--an appreciation". www.cobracountry.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ "Go Like Hell: Ford, Ferrari and Their Battle for Speed and Glory at Le Mans – Book Review". 9 September 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ Spinelli, Mike (17 May 2012). "How Carroll Shelby And A Gang Of Nerds Beat Enzo Ferrari". Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ "Ford Preparing to 'Go Like Hell!' at Le Mans 24 Hours". performance.ford.com. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ Baime, A. J. (2010). Go Like Hell: Ford, Ferrari, and Their Battle for Speed and Glory at Le Mans (Reprint ed.). Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0547336053.

- ^ Pete, Sneaky. "What happened to the movie adaptation of "Go Like Hell?"". Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ "Tom Cruise, 'Oblivion' Director Joseph Kosinski to Reteam for Fox's 'Go Like Hell'". 23 October 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ "Go Like Hell". Goodreads. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ The 24 Hour War, retrieved 1 April 2017

- ^ "Adam Carolla's 'The 24 Hour War' Is a Car Movie by Car People That Isn't Just for Car People". Road & Track. 18 January 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.2

- ^ Spurring 2010, p.171

- ^ Moity 1974, p.176

- ^ "Le Mans 24 Hours 1966 - Race Results". World Sportscar Championship. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Challenge Mondiale". Racing Sports Cars.com. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

References

- Armstrong, Douglas, English editor (1967) Automobile Year #14 1966–67 Lausanne: Edita S.A.

- Clarke, R.M., editor (1997) Le Mans 'The Ford and Matra Years 1966–1974' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-373-1

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Fox, Charles (1973) The Great Racing Cars & Drivers London: Octopus Books Ltd ISBN 0-7064-0213-8

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Moity, Christian (1974) The Le Mans 24 Hour Race 1949–1973 Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton Book Co ISBN 0-8019-6290-0

- Spurring, Quentin (2010) Le Mans 1960–69 Yeovil, Somerset: Haynes Publishing ISBN 978-1-84425-584-9

External links

- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1966 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 20 March 2018

- Le Mans History – Le Mans History, hour-by-hour (incl. pictures, YouTube links). Retrieved 20 March 2018

- World Sports Racing Prototypes – results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 20 March 2018

- Team Dan – results & reserve entries, explaining driver listings. Retrieved 20 March 2018

- Unique Cars & Parts – results & reserve entries. Retrieved 20 March 2018

- Formula 2 – Le Mans results & reserve entries. Retrieved 20 March 2018

- YouTube "This Time Tomorrow" – Colour film by Ford about their race (30mins). Retrieved 8 April 2018

- YouTube "Eight Metres" – Colour film about the race & the finish (30mins). Retrieved 8 April 2018

- YouTube – Colour film about the start & the finish (5mins). Retrieved 8 April 2018

- YouTube – Silent b/w footage including start (2mins). Retrieved 8 April 2018

- YouTube "British Pathé" – Silent b/w footage including start (2mins). Retrieved 8 April 2018

- YouTube – modern footage interviewing the pit crew of Ford #1 (5mins). Retrieved 8 April 2018